2 Stress

Having reviewed static equilibrium in Chapter 1, we know how to find the internal loads in a body using equilibrium. When determining whether a body can resist the loads applied to it, keep in mind that the internal load is only part of the solution. The dimensions of the body and the inherent properties of the material it is made from are also important.

In this chapter we explore the concept of stress, which can help us determine whether an object will physically break when subjected to a load. We cover average normal stress (stress perpendicular to the cross-section) in Section 2.1 and average shear stress (stress parallel to the cross-section) in Section 2.2. We then discuss bearing stress (the stress between two bodies in contact with each other) in Section 2.3 and finish with the average normal and shear stresses on an inclined cross-section in Section 2.4.

2.1 Average Normal Stress

Click to expand

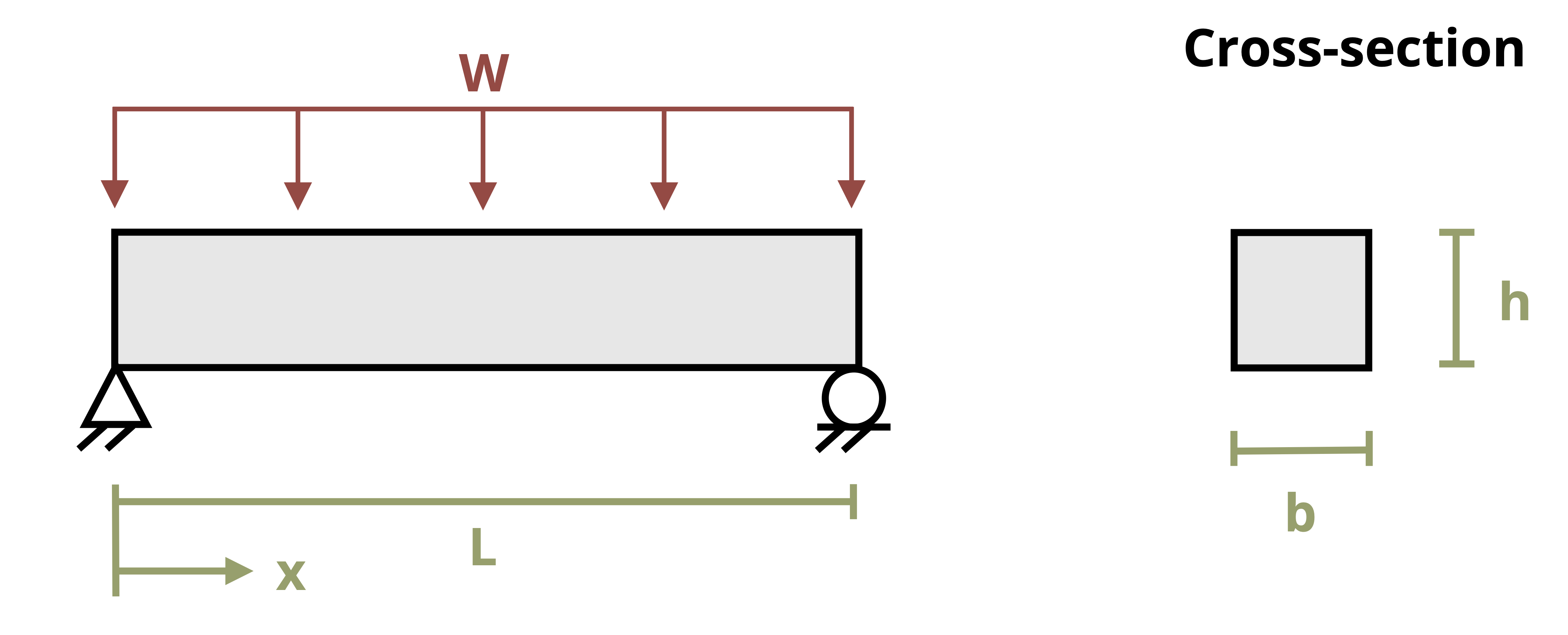

Average normal stress is defined as the internal normal force divided by the cross-sectional area of the body. By convention, it is represented by the Greek letter sigma (σ). Stress increases as the force increases or as the cross-sectional area decreases.

\[ \boxed {\sigma=\frac{N}{A}}\text{ ,} \tag{2.1}\]

𝜎 = Average normal stress [Pa, psi]

N = Internal normal force [N, lb]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

As such the SI units of stress are N/m2, more commonly referred to as the Pascal (Pa), where 1 Pa = 1 N/m2. The US customary units for stress are lb/in.2, commonly written as psi, which is short for pounds per square inch. Since stresses can get very large, it is common to use prefixes such as kilo (k) and mega (M) to represent 103 and 106 respectively. A stress of 15,000,000 Pa is written as 15 MPa. A stress of 35,000 psi is written as 35 ksi.

Normal stress occurs perpendicular to the cross-section and so is associated with either a pulling or pushing motion (Figure 2.1). Normal forces that pull on a cross-section are known as tensile forces and create a tensile normal stress. Normal forces that push on a cross-section are known as compressive forces and create a compressive normal stress. By convention, tensile normal forces and stresses are positive, while compressive normal forces and stresses are negative.

The normal stress calculated above is really an average normal stress because the force is distributed over the cross-section, but it can generally be simplified as a concentrated force that creates the same normal stress at every point on the cross-section (Figure 2.2).

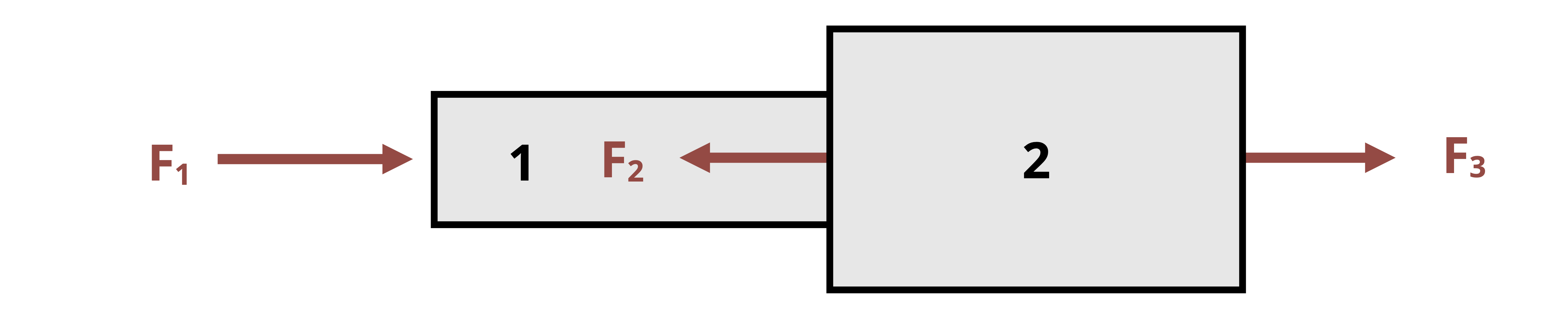

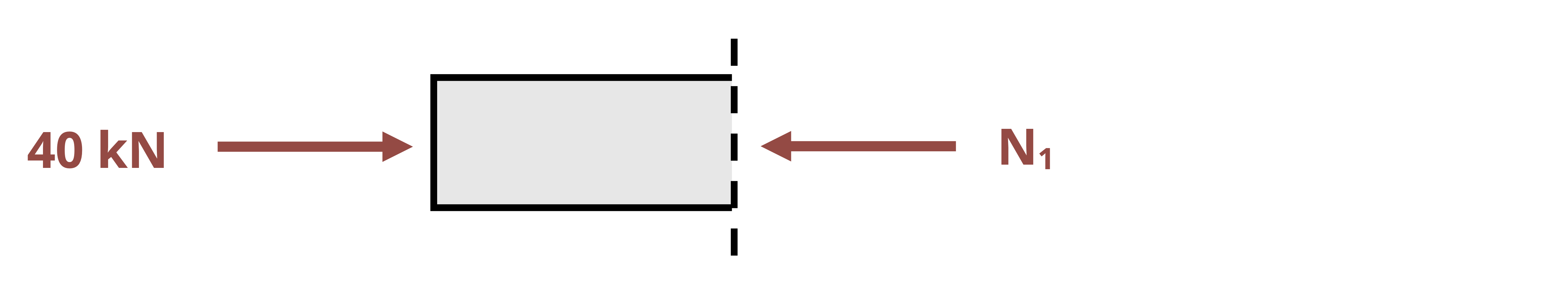

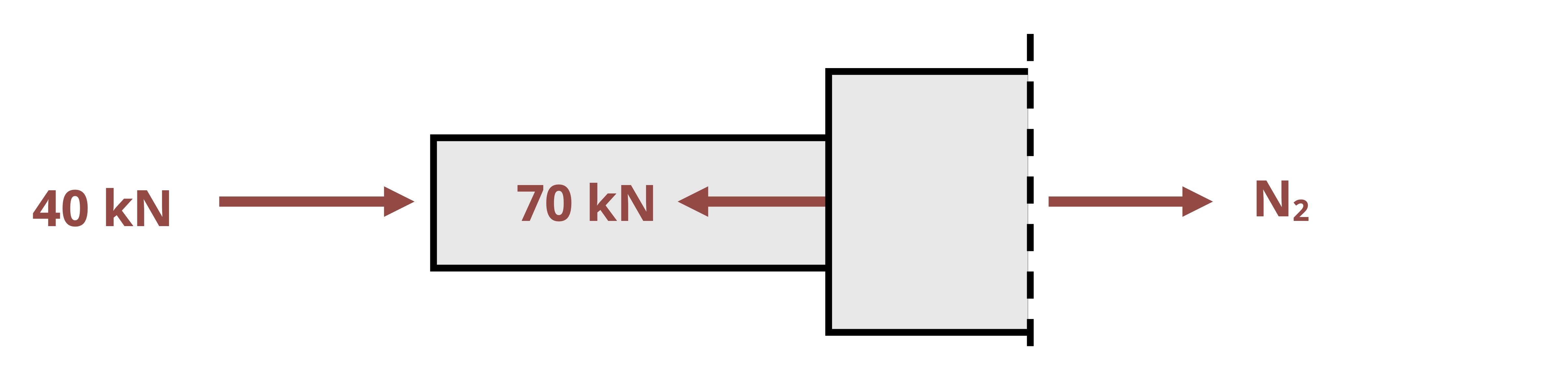

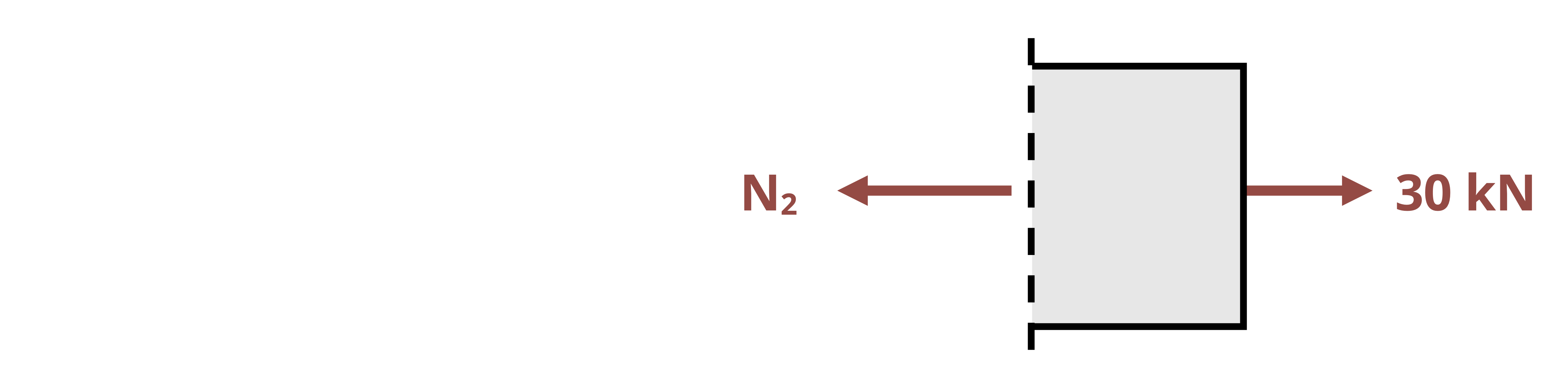

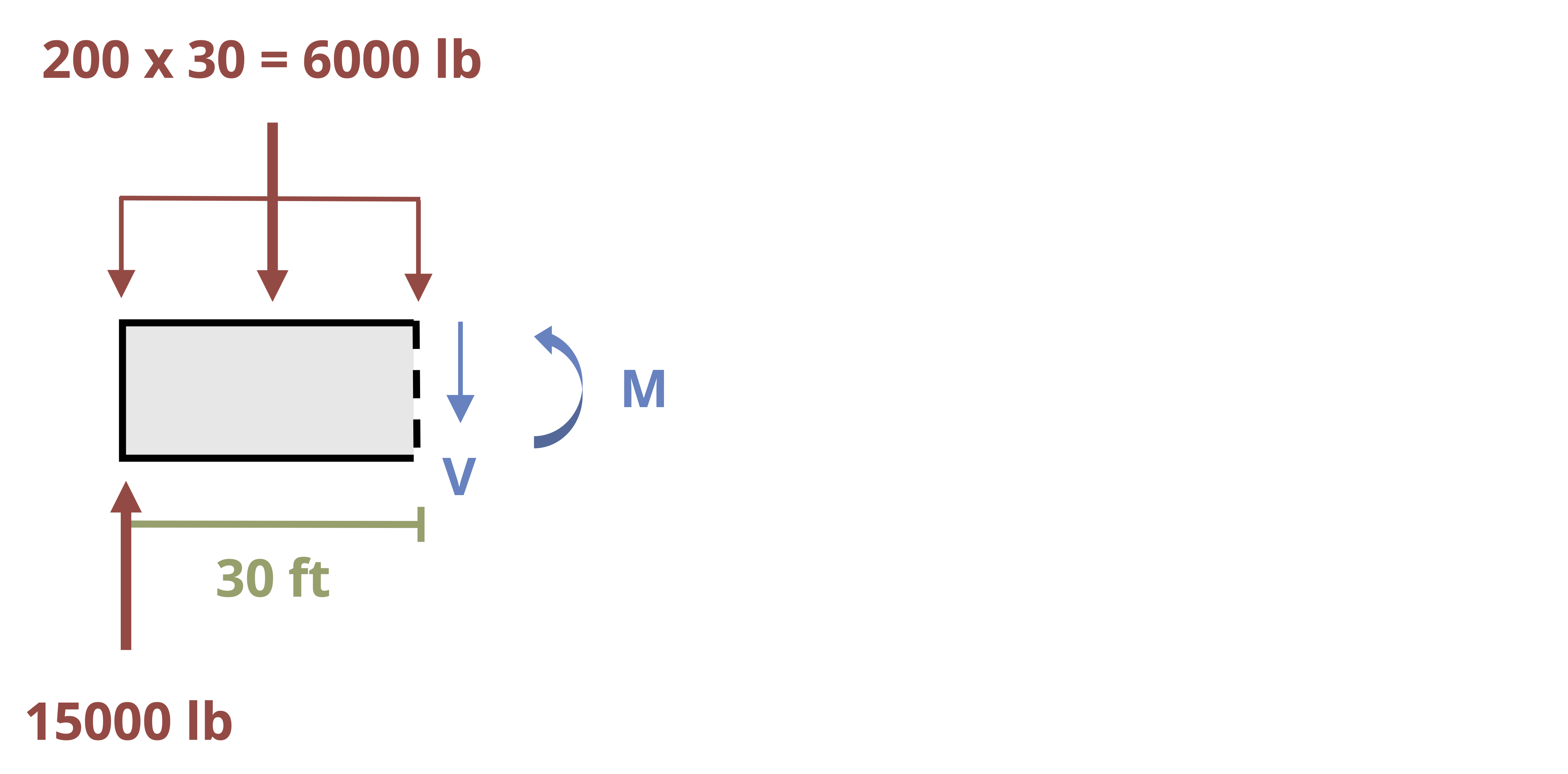

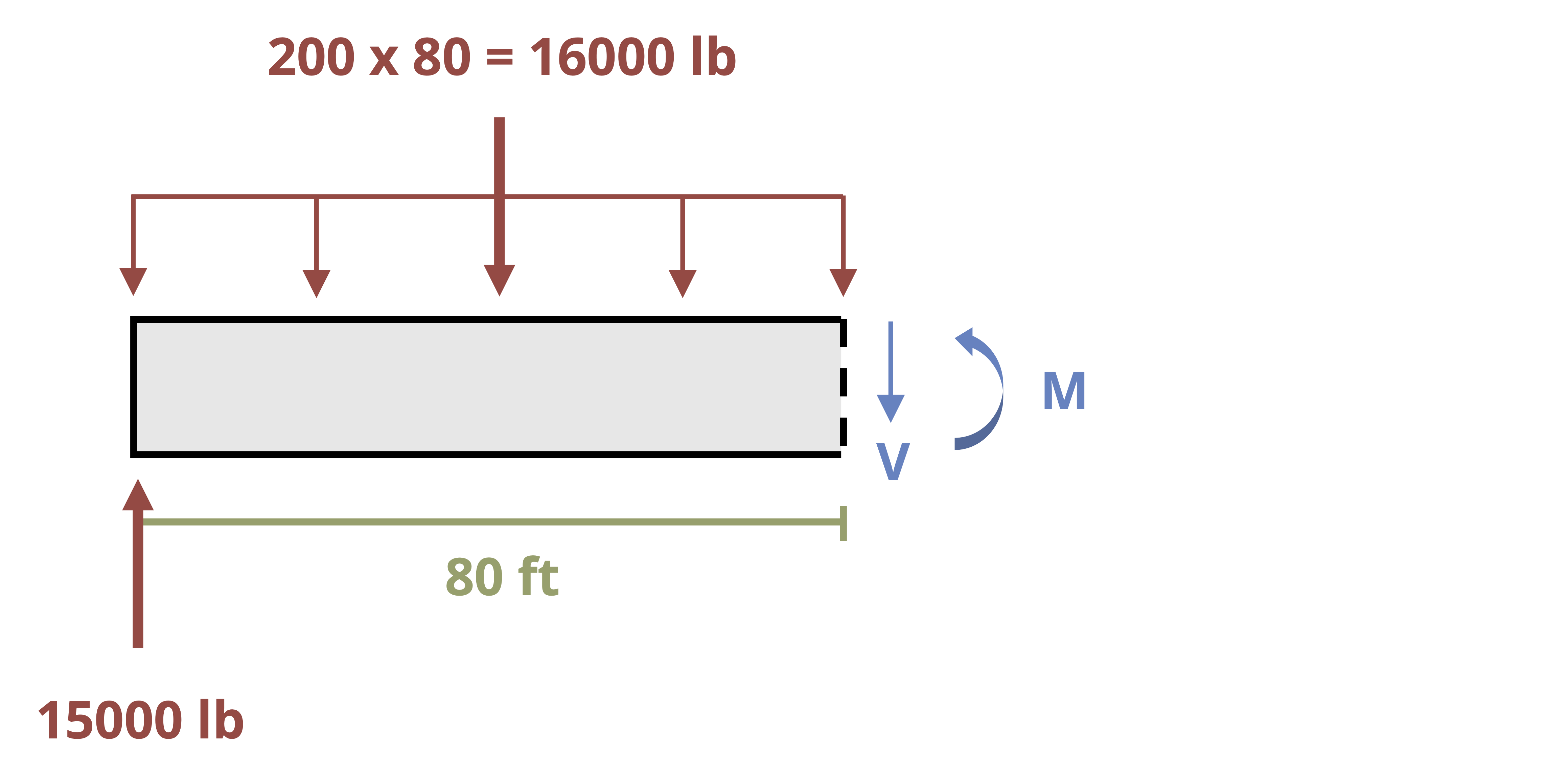

The internal normal force in a body can be found through the method of equilibrium as reviewed in Section 1.2. See Example 2.1 for a demonstration.

Sometimes the loading or cross-sectional area will not be the same at different points in the body, resulting in different stresses. In these cases the stress can be calculated separately in each segment of the body by first finding the internal load in each segment and then dividing the internal load by the cross-sectional area of the respective segment. Different parts of the body may experience different stresses. Generally, the highest stress is of most importance, as that is the stress that typically determines whether the body will break. Because we don’t know in advance where the largest stress is, however, it is typically necessary to calculate the stress at each cross-section to determine the highest stress. See Example 2.2 for a demonstration.

2.2 Average Shear Stress

Click to expand

Average shear stress is defined as the internal shear force divided by the cross-sectional area of the body. While normal forces (and therefore normal stresses) occur when a body is under tension or compression, shear forces (and therefore shear stresses) occur when a force is tangentially applied parallel to the cross-section, resulting in a sliding motion (Figure 2.3).

Although the basic definition of average normal stress and average shear stress is the same—force divided by area—there are some differences. To differentiate which stress we’re talking about, we denote shear stress by the Greek letter tau (τ).

\[ \boxed{\tau=\frac{V}{A}}\text{ ,} \tag{2.2}\]

τ = Average shear stress [Pa, psi]

V = Internal shear force [N, lb]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

Like normal force, internal shear force can be found by cutting a cross-section through the body, drawing an FBD, and applying equilibrium equations. See Example 2.3 for a demonstration.

Shear stresses are common in both members of a structure and also in the fasteners between members. Depending on how these connections are formed, we may see multiple shear planes. It is very important to correctly identify the internal force in the body. Figure 2.4 demonstrates the difference between single and double shear configurations for a pinned joint and the effects on internal shear force. Notice that in the case of double shear, the internal shear force is half that of the applied force, F1. See Example 2.4 for an example of double shear.

2.3 Bearing Stress

Click to expand

Bearing stress is similar to normal stress, except that it occurs at the contact area between two bodies instead of within a single body. Bearing stress is calculated with the average normal stress equation, where the cross-sectional area is the contact area between the two bodies (Figure 2.5).

One common situation is contact between two curved edges, such as the bolt in Figure 2.6. In this situation it is common to use the projected contact area between the curved surfaces, which forms a rectangle of base d and height t.

\[ A=d*t \]

This greatly simplifies the calculation but again represents an average value for the contact or bearing stress. See Example 2.5 for a problem involving the bearing stress between a bolt and a plate.

2.4 Stress on an Inclined Plane

Click to expand

We have so far been cutting cross-sections perpendicular to the external force or parallel to it. However, no rule says we have to do this. It is perfectly acceptable to cut cross-sections at an angle, and in many situations it may make sense to do so (Figure 2.7).

In this scenario, to maintain equilibrium the internal load must still be equal and opposite to the external load, but because the cross-section is cut at an angle, this internal load is neither parallel nor perpendicular to the cross-section. Therefore, it is not entirely a normal force or a shear force. However, the internal force may be broken into components that are perpendicular and parallel to the cross-section.

\[ \begin{aligned} & N=P \sin (\theta) \\ & V=P \cos (\theta) \end{aligned} \]

The area used to calculate the average normal and shear stresses must be the area of the inclined plane (Figure 2.8). Setting up a right-angled triangle enables us to find the area of the plane, Ap.

\[ A_p=\frac{A}{\sin (\theta)} \]

We can then calculate average normal stress.

\[\boxed{\sigma=\frac{N}{A_p}=\frac{P \sin (\theta)}{\frac{A}{\sin (\theta)}}=\frac{P \sin ^2(\theta)}{A}} \tag{2.3}\]

We can calculate average shear stress from

\[\boxed{\tau=\frac{V}{A_p}=\frac{P \cos (\theta)}{\frac{A}{\sin (\theta)}}=\frac{P \sin (\theta) \cos (\theta)}{A}}\text{ ,} \tag{2.4}\]

𝜎 = Average normal stress on the inclined plane [Pa, psi]

τ = Average shear stress on the inclined plane [Pa, psi]

N = Internal normal force perpendicular to the inclined plane [N, lb]

V = Internal shear force parallel to the inclined plane [N, lb]

Ap = Area of the inclined plane [m2, in.2]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

P = Internal load perpendicular to cross-sectional area A [N, lb]

𝜃 = Angle between the inclined plane and the axis perpendicular to cross-sectional area A [°]

These equations assume the angle (θ) is measured from the axis perpendicular to area A. For a horizontal beam, area A is in the vertical plane, so angle θ is measured from the horizontal axis.

Even if the external load remains constant, we can obtain different values for the internal normal and shear forces (and therefore different values for the stresses) by changing the angle at which we cut the cross-section. Chapter 12 explores the implications. For now, a demonstration of calculating the stresses on an inclined plane is given in Example 2.6.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

Figure 2.1: Forces pulling on a cross-section cause tension, while forces pushing on a cross-section cause compression. Left image: Orangeaurochs. 2012. CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/dqmXdM. Right image: Unknown author. 2017. Public domain. https://pxhere.com/en/photo/993074. Diagrams: Kindred Grey. 2024. CC BY.

Example 2.1: Jbarta. 2010. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Permanent-column-form.jpg.

Example 2.4: Image: James Lord. CC BY NC-SA.

Figure 2.5: Circular column sitting upon a rectangular foundation. Jiří Sedláček - Frettie. 2010. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Footing_of_column_in_collections_of_Muzeum_Vyso%C4%8Diny_in_T%C5%99eb%C3%AD%C4%8D,_T%C5%99eb%C3%AD%C4%8D_District.jpg.

.png)