5 Axial Loading

This chapter takes a closer look at the effects of axial loading. Axial loads are those applied perpendicular to the cross-section of an object (Figure 5.1). Such loads affect the object in several ways.

Axial loads create axial stresses, as seen in Section 2.1 and revisited briefly in Section 5.1. We previously considered the average normal stress in a cross-section, but the geometry of the cross-section can cause large localized stresses much higher than the average. These stress concentrations are discussed in Section 5.2.

This text is concerned with both stress and deformation, so Section 5.3 explores the deformation caused by axial loads. This extends to a special case of axial deformation involving parallel bars in Section 5.4, before we apply our knowledge of axial deformation to solve statically indeterminate problems in Section 5.5. These are problems where the equilibrium equations are insufficient to determine the reaction and internal forces.

Finally we’ll investigate the effects of temperature in Section 5.6. As the temperature of an object changes, the object expands or contracts. Thus deformation can occur even in the absence of any applied forces.

5.1 Axial Stress

Click to expand

Axial loads create axial stresses, also known as normal stresses. As discussed in Section 2.1, the average normal stress is calculated from

\[ \boxed {\sigma=\frac{N}{A}}\text{ ,} \]

𝜎 = Average normal stress [Pa, psi]

N = Internal normal force [N, lb]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

5.2 Stress Concentrations

Click to expand

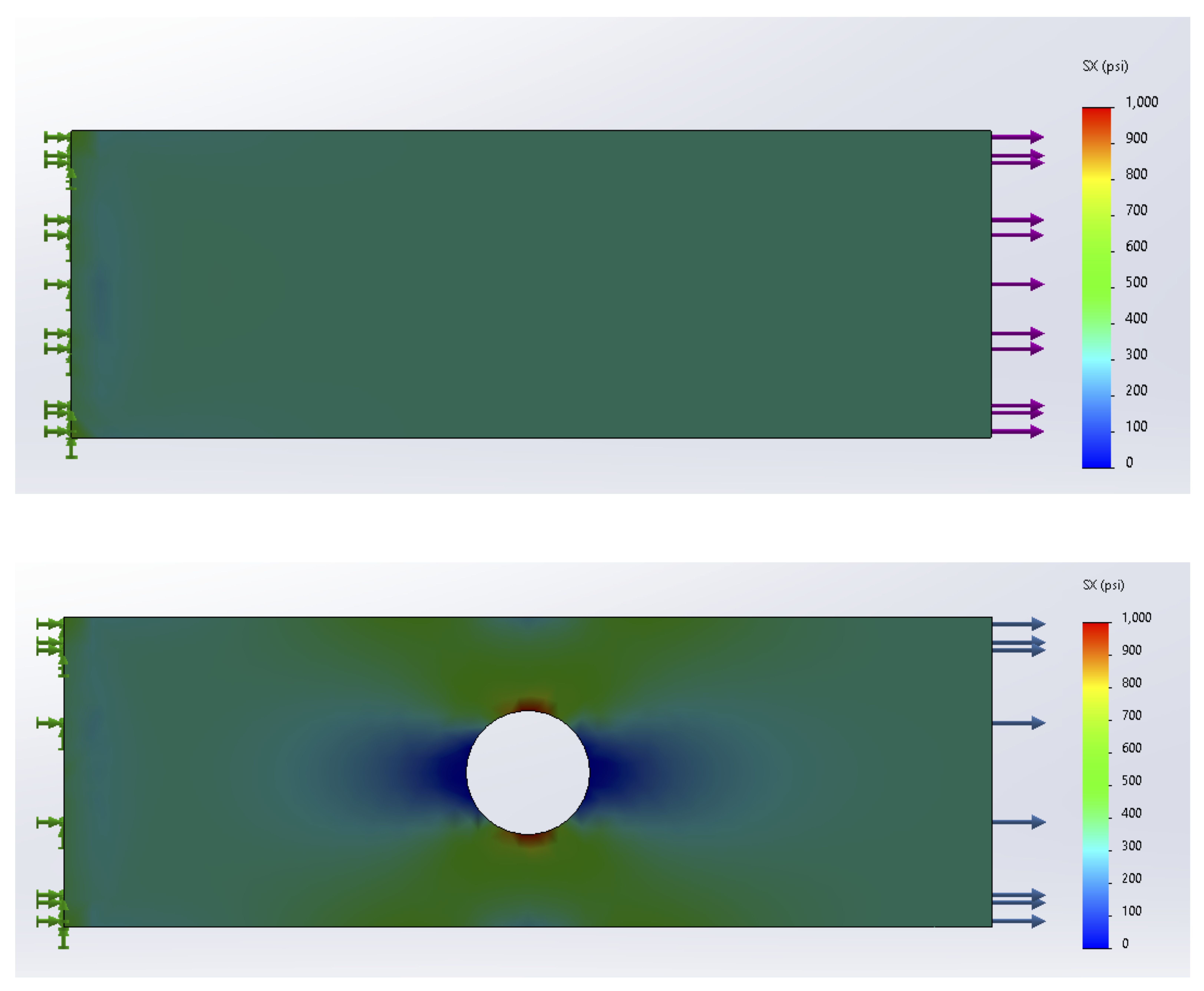

5.2.1 Saint-Venant’s Principle

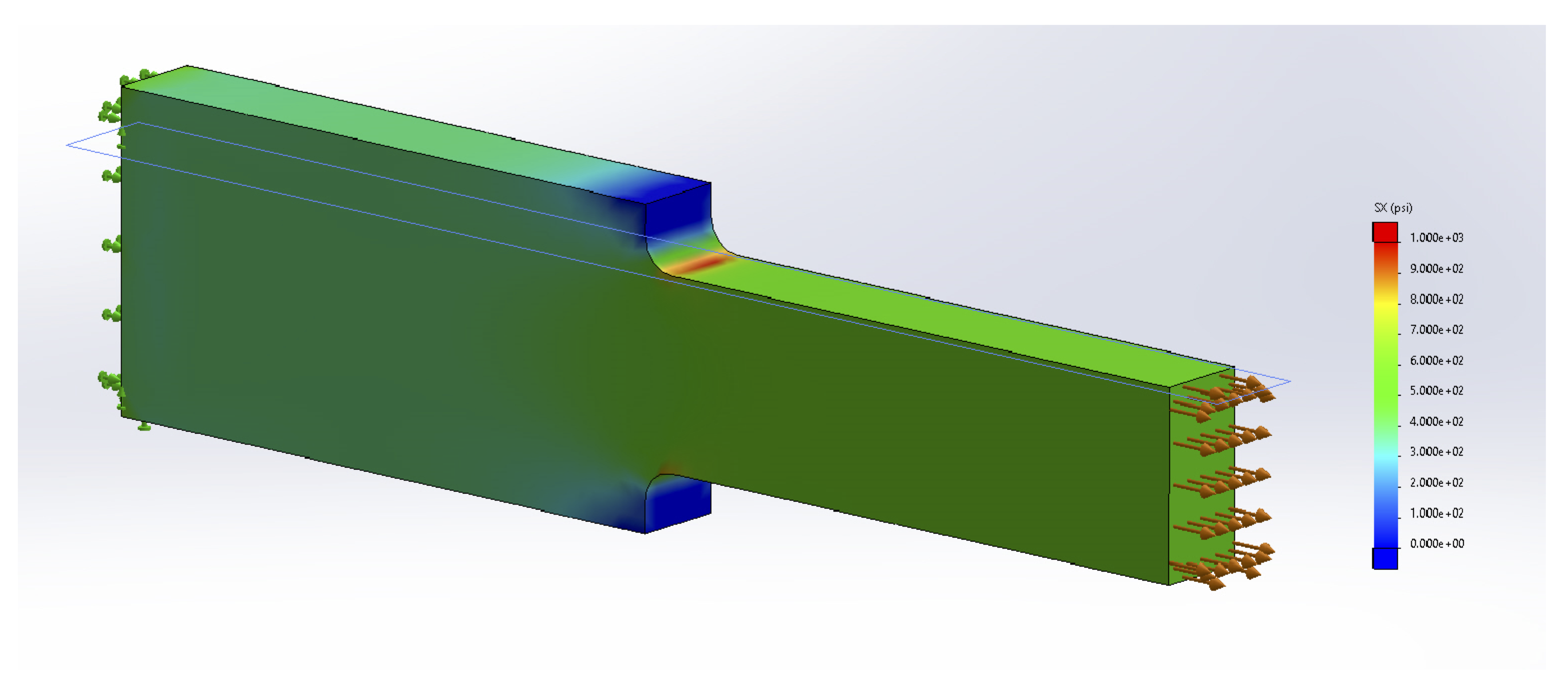

The normal stress mentioned in the introductory section is averaged over the cross-section and assumes that stresses (and therefore strains) at the cross-section are uniform. In reality stresses and strains can vary across a cross-section, especially if the cross-section is close to an applied load, a support, or a change in geometry. At these points localized stress concentrations occur, leading to large, localized stresses and strains. The intensity of these concentrations depends on the type of loading, support, or geometry (Figure 5.2).

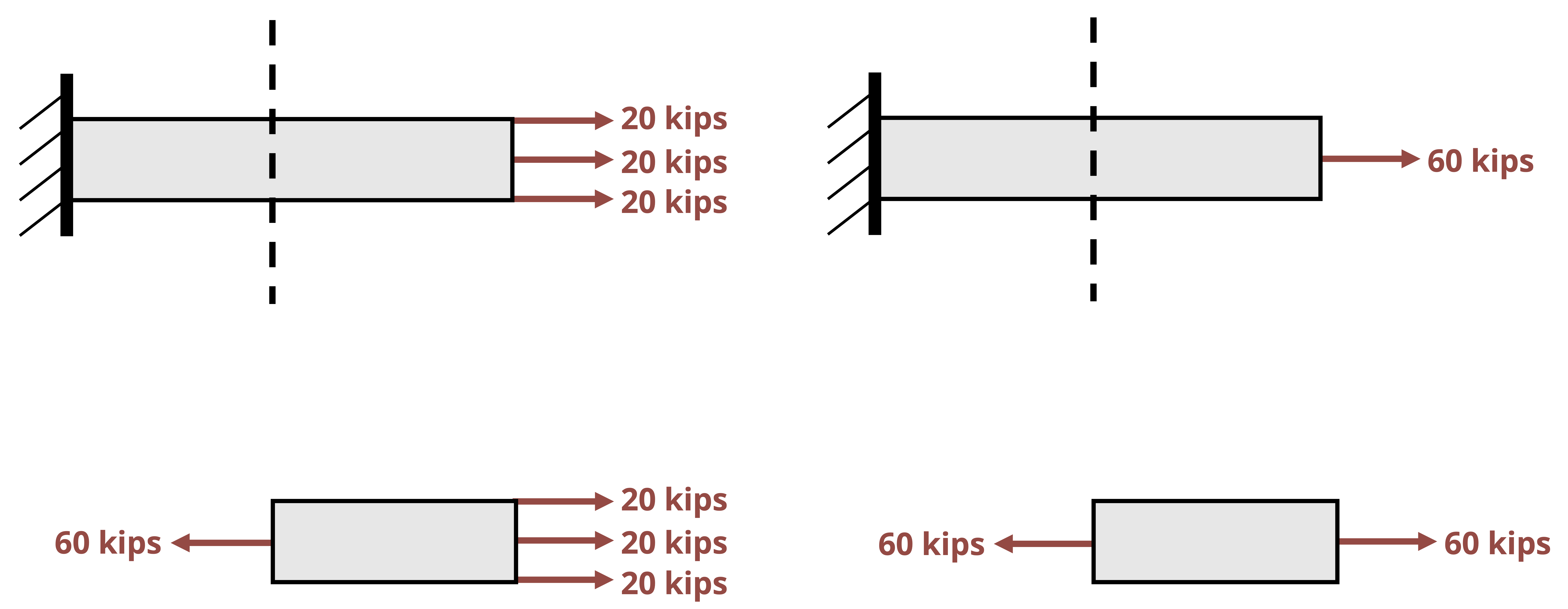

However, these effects disappear a certain distance away from the force, support, or local geometry, so it is acceptable to assume uniform stress and strain (as we have done so far) provided that we also assume our cross-section is a sufficient distance away from these points. This is known as Saint-Venant’s principle, which can be formally stated thus: “The stresses and strains created at a point in a body by two statically equivalent loads are equivalent at points sufficiently far removed from the applied load” (Figure 5.3).

5.2.2 Stress Concentrations Around Changes in Geometry

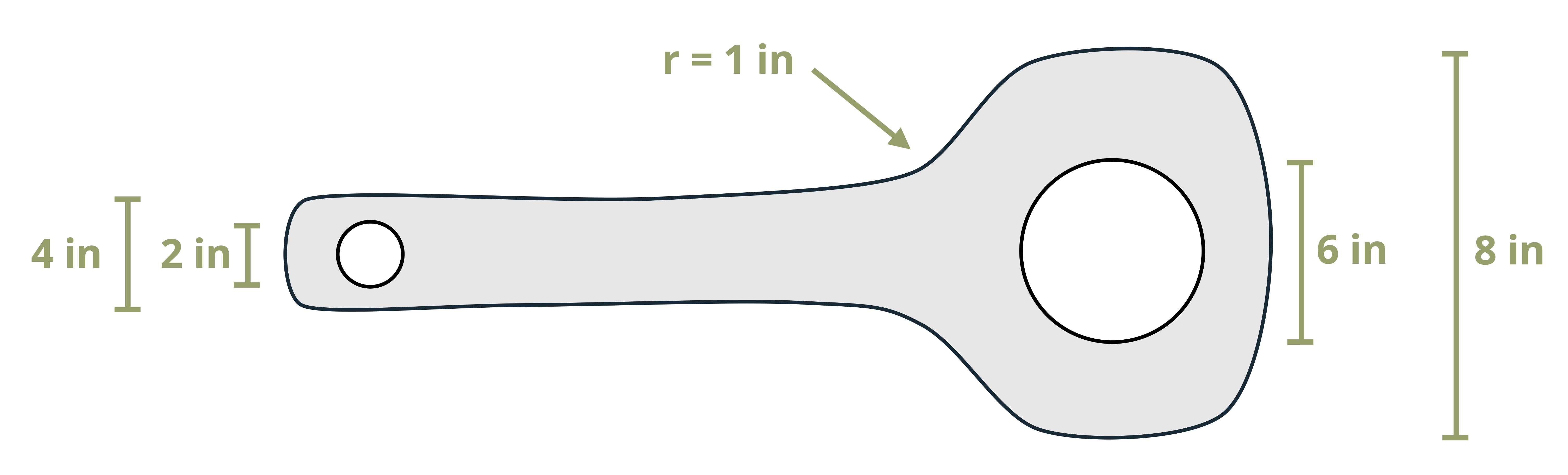

More advanced courses use the theory of elasticity to study the areas of variable stress and strain, but for now we’ll continue to apply Saint-Venant’s principle and assume that our cross-sections are sufficiently far away from the applied loads to eliminate the need to consider these stress concentrations. Here, however, the focus is on the question of stress concentrations around changes in geometry. We’ll study two specific examples; holes and fillets. Figure 5.2 shows an example of the stress concentrations around a hole. Figure 5.4 shows an example of the stress concentrations around a fillet, which is a rounded corner used to help transition between two geometries.

Fully modeling these stress concentrations is very complicated, but for our purposes it is sufficient to find only the maximum stress that occurs around these stress concentrations. These can be significantly larger than the average stress we have been calculating and can cause localized failure even if the average stress is below the yield stress for the material. The maximum stress can be found simply by multiplying the average stress by a stress concentration factor, K.

\[ \boxed{\sigma_{max}=K \sigma_{avg}}\text{ ,} \tag{5.1}\]

𝜎max = Maximum normal stress [Pa, psi]

K = Stress concentration factor

𝜎avg = Average normal stress [Pa, psi]

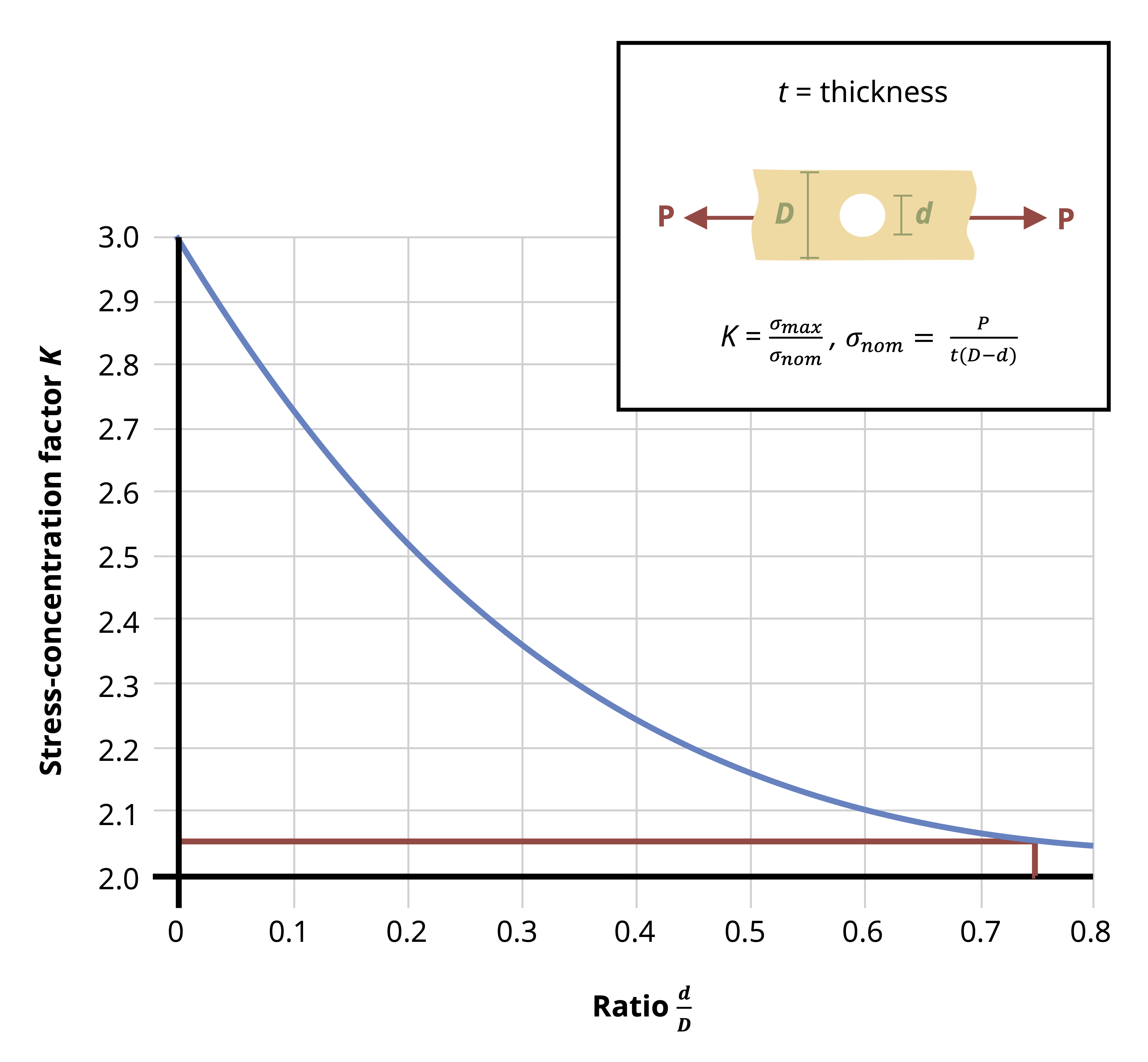

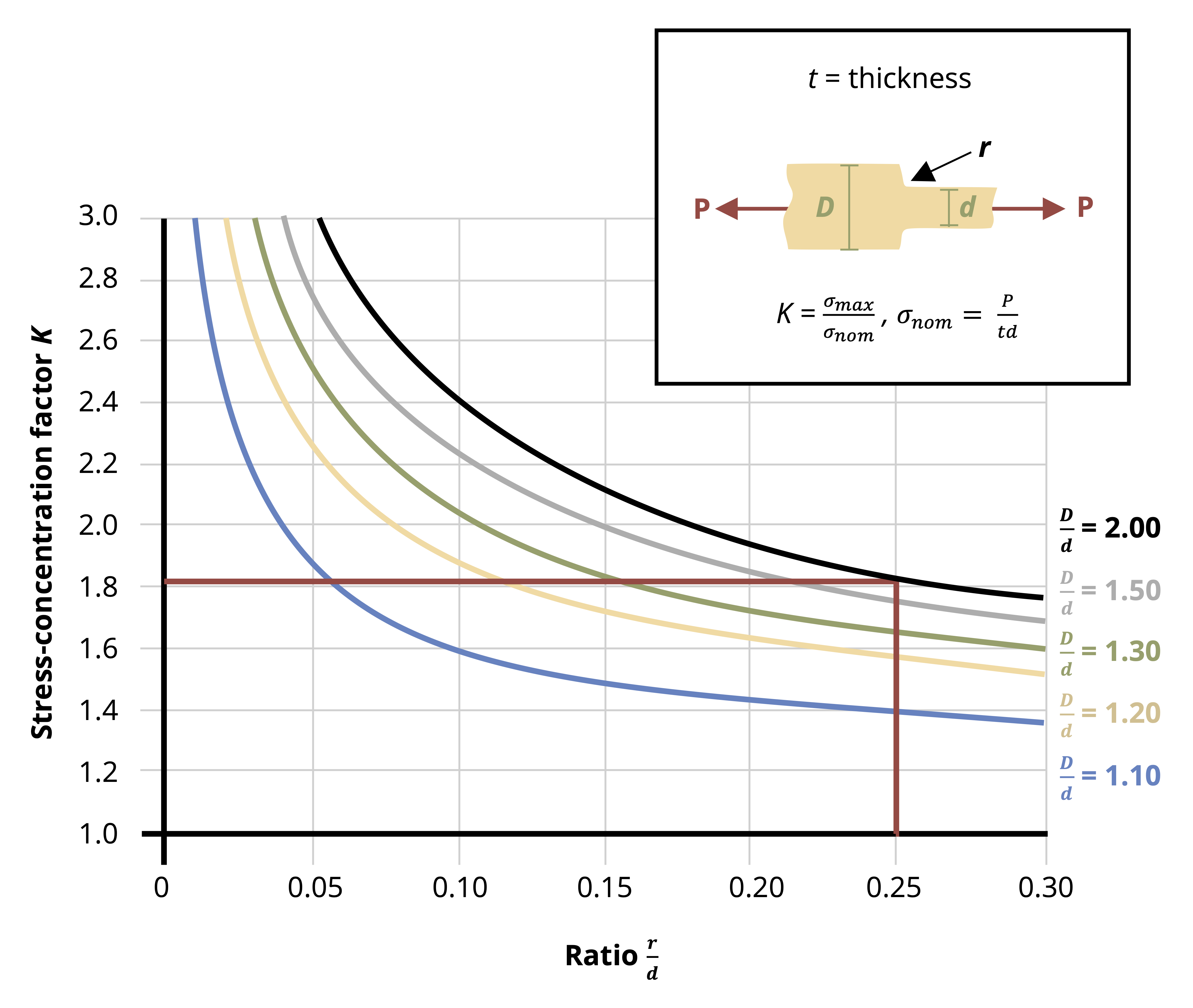

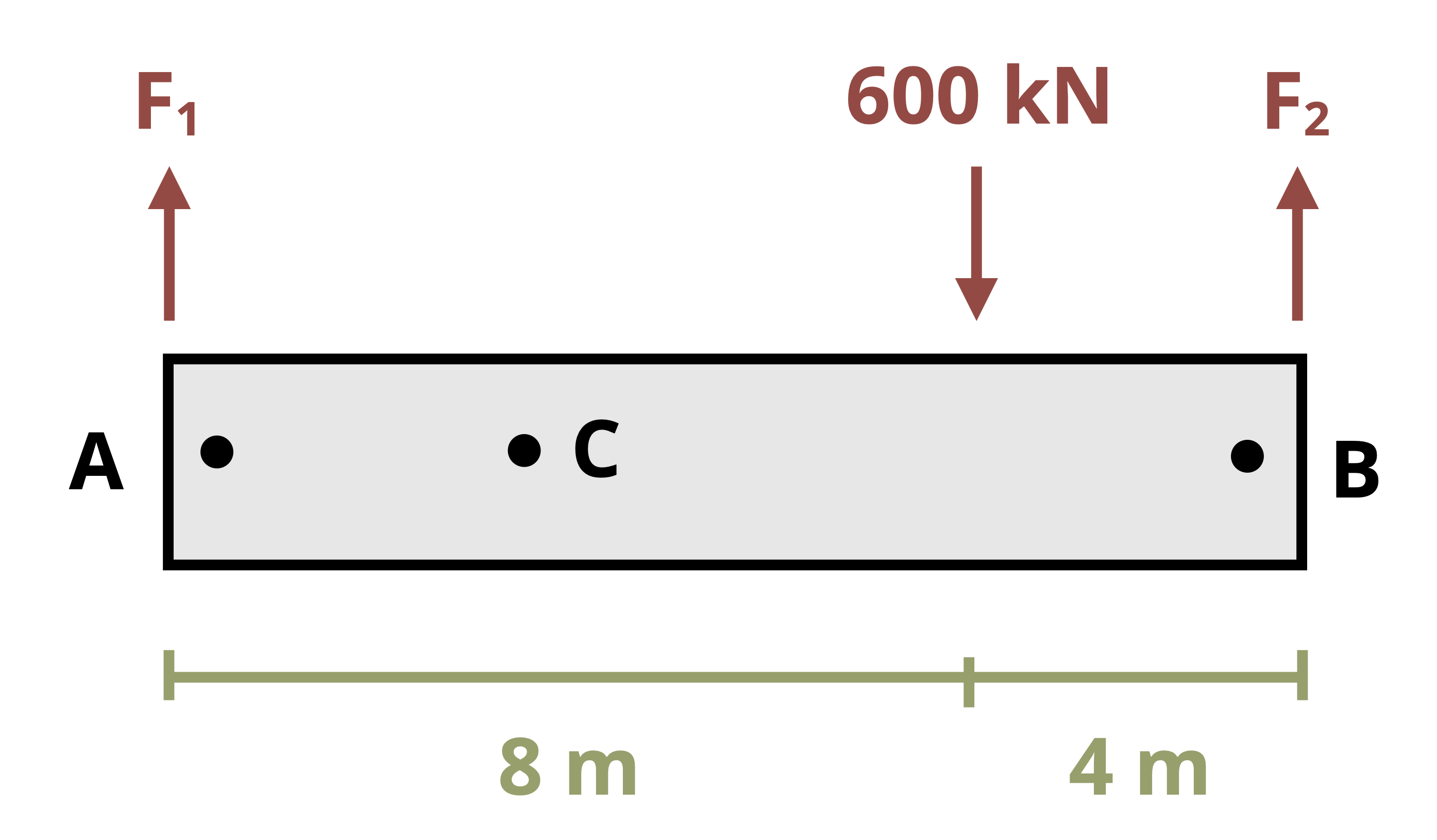

This stress concentration factor depends on the geometry at hand and can be found from curves in design handbooks. Figure 5.5 shows curves for holes and fillets. The average normal stress is calculated at whichever plane gives the largest value. For the case with a hole, this is the plane passing through the center of the hole. For the case with a fillet, this is a plane passing through the smaller segment of the member. See Example 5.1 and Example 5.2 to see how these curves can be used.

![Two charts that compare stress concentration factors for tension members with geometric changes. On the left, a flat plate with a central circular hole is shown in the inset. The plate has a total width D, a hole of diameter d, and thickness t, with equal tensile loads P applied at both ends. The inset also includes the equations: K = sigma sub max / sigma sub avg and sigma sub average = P / [t × (D − d)]. The vertical axis shows the stress concentration factor K, and the horizontal axis shows the ratio d / D. The single curve starts near K = 3 when d / D = 0 and gradually decreases toward about K = 2 as d / D increases, showing that larger holes relative to plate width lead to lower stress concentration factors. On the right, the inset shows a stepped bar with a fillet radius r connecting a large diameter D to a smaller diameter d. The inset also includes the equations: K = sigma sub max / sigma sub average and sigma sub average = P / (t × d). The vertical axis again shows K, and the horizontal axis shows the ratio r / d. Several colored curves represent different diameter ratios (D/d = 1.10, 1.20, 1.30, 1.50, and 2.00). Each curve decreases as r / d increases, indicating that larger fillet radii reduce stress concentration. For a given r / d, higher D/d ratios correspond to higher K values, meaning that a sharper diameter change produces greater stress concentration.](images/chapter 5 figure edits after review/figure 5.5.png)

Apparent from these examples is that sharp corners and tight radii lead to high stress concentrations. When designing parts, it is best to use smooth, flowing transitions where possible and avoid sharp corners to minimize stress concentrations.

5.3 Axial Deformation

Click to expand

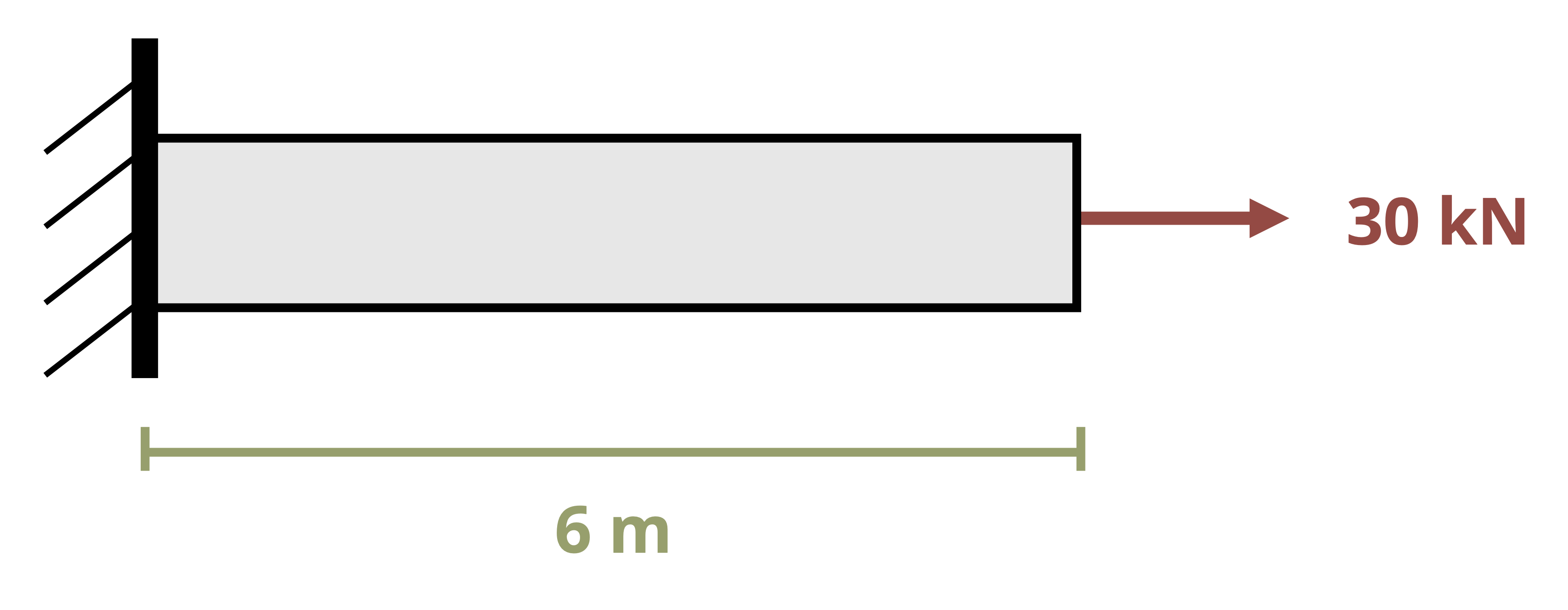

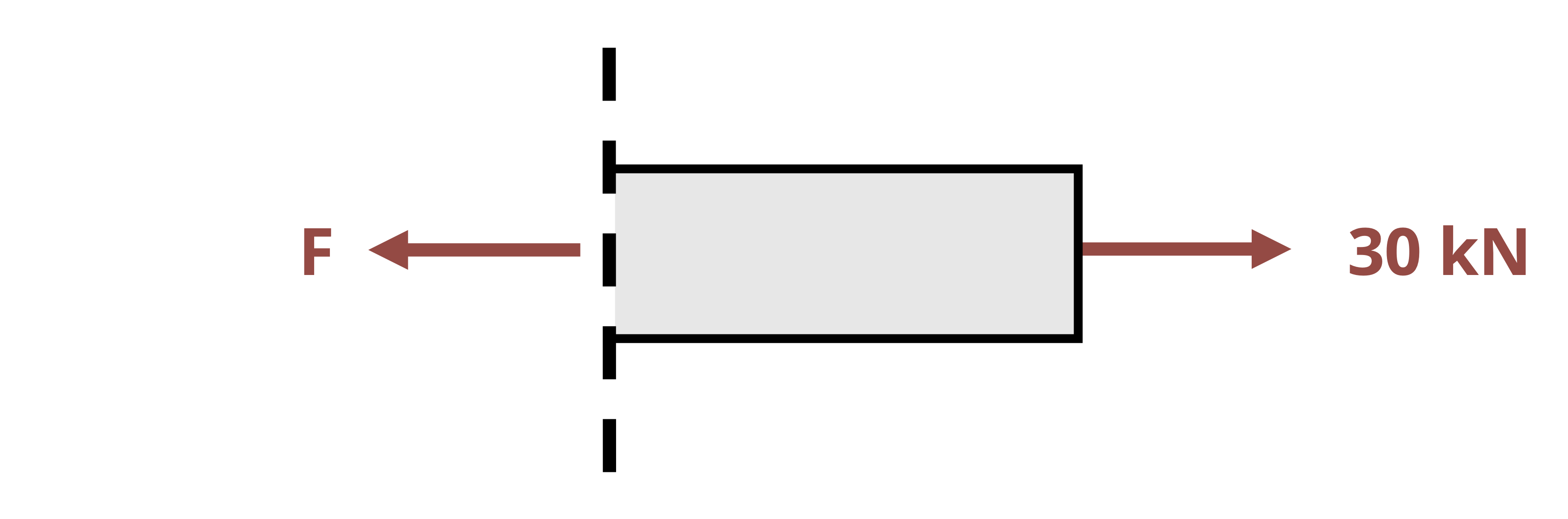

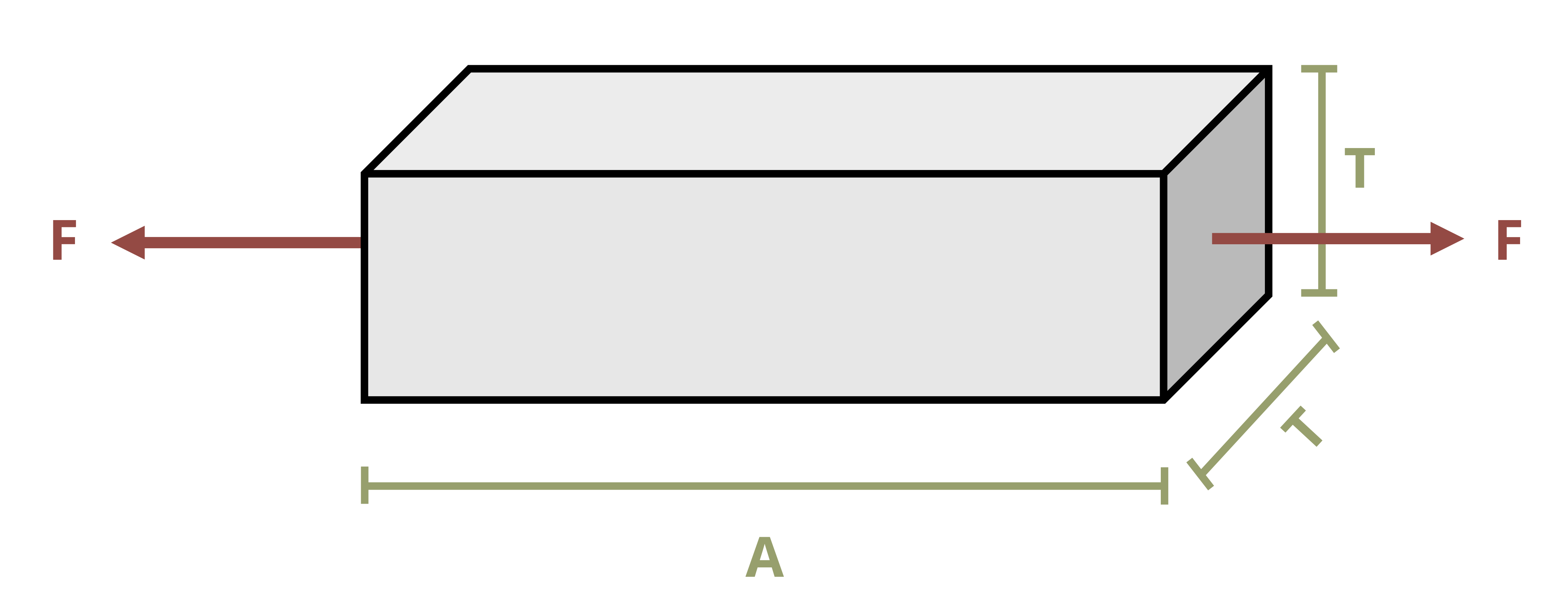

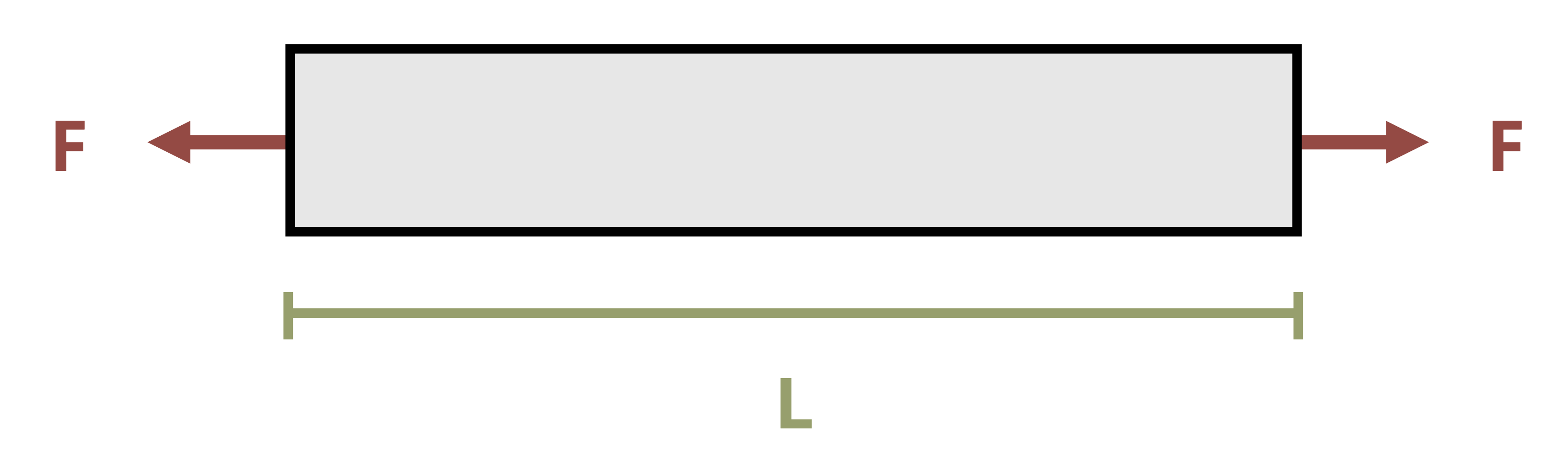

Consider a simple bar of uniform cross-section subjected to an axial force (Figure 5.6).

Assuming elastic behavior, we have equations for stress and strain, as well as Hooke’s law, which relates the two equations.

\[ \begin{aligned} & \sigma=\frac{F}{A} \\ & \varepsilon_{long}=\frac{\Delta L}{L} \\ & \sigma=E \varepsilon_{long}\end{aligned} \]

Replace the stress and strain terms in Hooke’s law.

\[ \frac{F}{A}=E \frac{\Delta L}{L} \]

Rearrange the equation.

\[ \Delta L=\frac{F L}{A E} \]

This last equation can be used to directly find the change in length of an object subjected to an axial load.

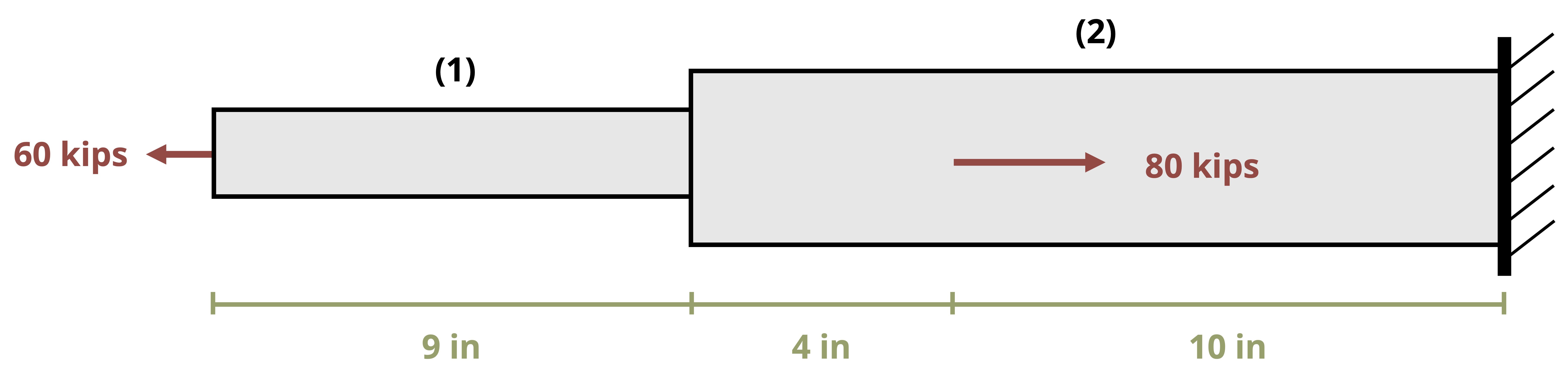

In practice, multiple axial loads may be applied to the bar. The cross-sectional area may change at different points along the bar, or perhaps different materials with different elastic moduli are connected in series to form the bar. In any of these cases we can split the bar into sections where each section has a constant F, A, and E. We can calculate the change in length of each section separately and sum them to find the total. See Example 5.3 for deformation of a simple bar subjected to a single load and Example 5.4 for a problem involving multiple segments of a bar.

\[ \boxed{\Delta L=\sum \frac{F L}{A E}}\text{ ,} \tag{5.2}\]

ΔL = Change in length [m, in.]

F = Internal axial load [N, lb]

L = Original length [m, in.]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

E = Elastic modulus [Pa, psi]

5.4 Deformation in Series of Bars

Click to expand

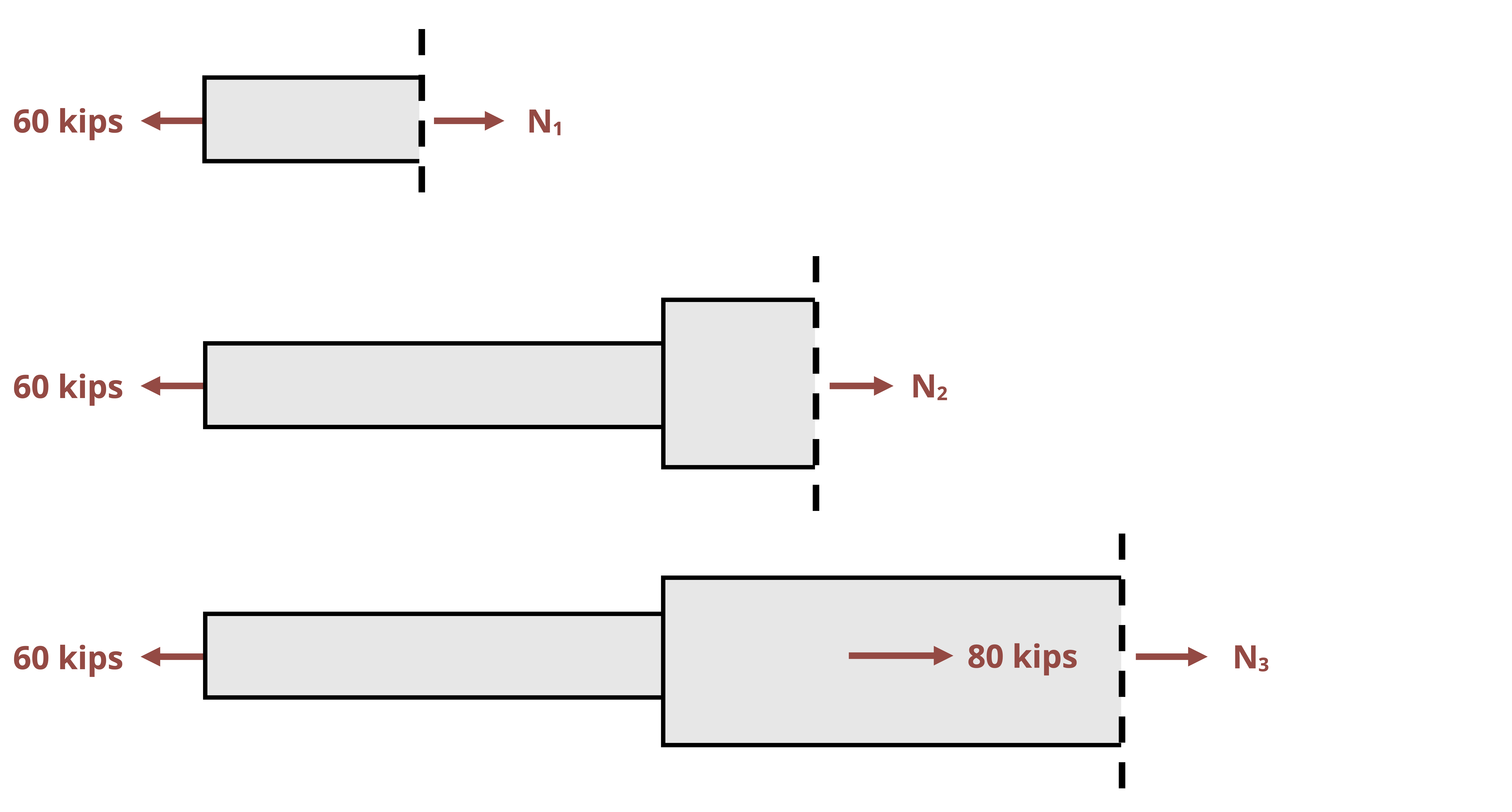

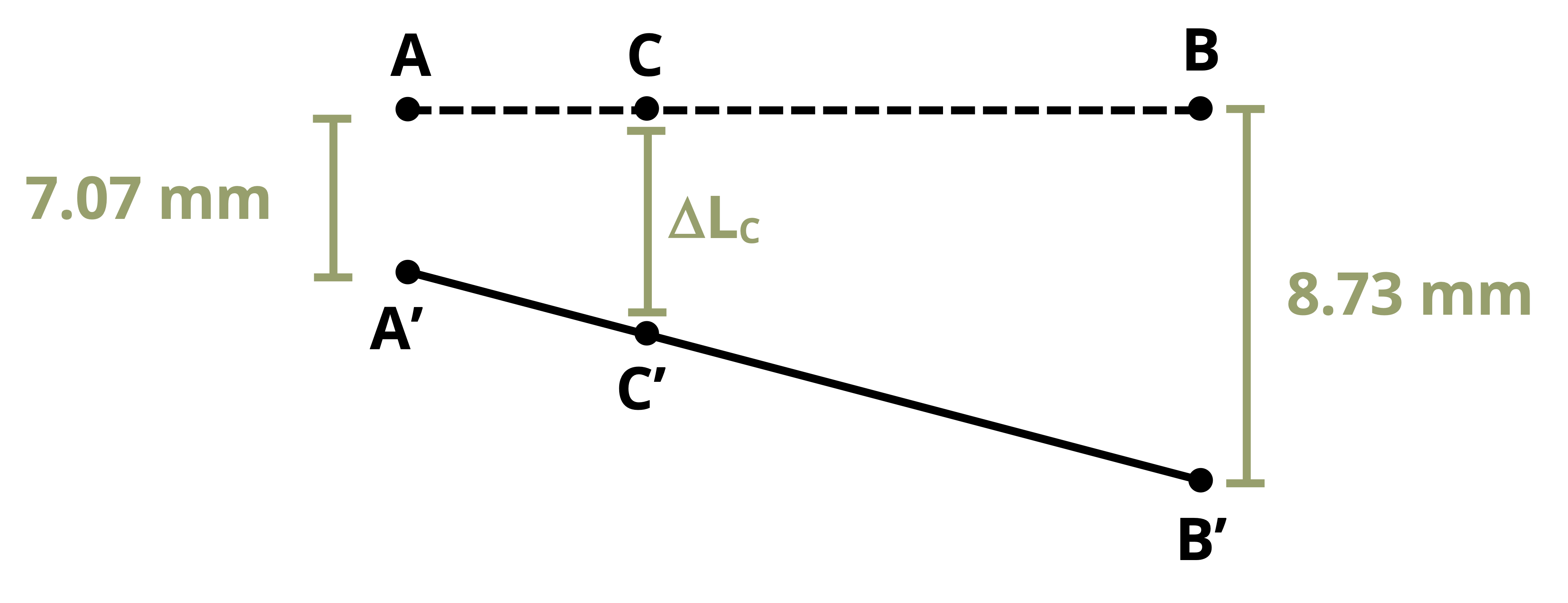

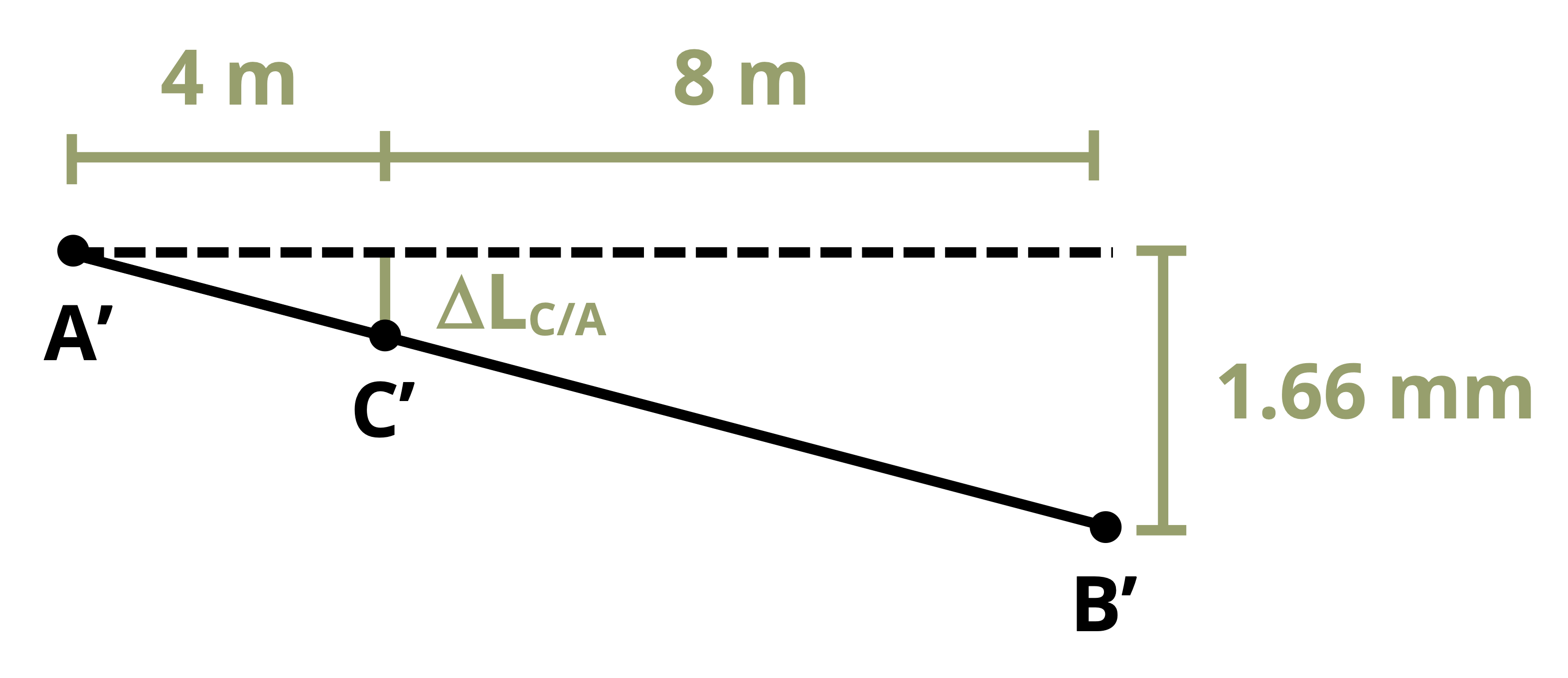

Sometimes a structure has more than one axially loaded member. In such cases multiple bars will experience a change in length and the amount of deformation won’t necessarily be the same in each member. The deformable members are generally connected by a rigid (nondeformable) beam. These problems generally involve a little geometry alongside the deformation equation (Figure 5.7).

By identifying the force in each member through equilibrium, we may calculate the deformation of each member separately by using

\[ \Delta L=\frac{F L}{A E}\text{.} \]

Once each member’s change in length is known, use simple geometry to find the displacement at different points on the rigid beam (Figure 5.8). This process is demonstrated in Example 5.5.

The deflection of point C will be somewhere between the deflection at A and the deflection at B. Assuming that there is no deflection at A and that the deflections (and thus the angle at A) are small, use similar triangles to find

\[ \frac{\Delta L_C}{L_{A C}}=\frac{\Delta L_2}{L} \rightarrow \Delta L_C=\Delta L_2 \frac{L_{A C}}{L}\text{.}\]

If a deflection exists at point A (Figure 5.9), this simply becomes

\[ \Delta L_C=\Delta L_1+\left(\Delta L_2-\Delta L_1\right) \frac{L_{A C}}{L}\text{.}\]

5.5 Statically Indeterminate Problems

Click to expand

A statically indeterminate problem is one that has more unknowns than we have equilibrium equations to solve for them. This issue prevents us from finding the internal loads, and so we cannot calculate stress or deformation.

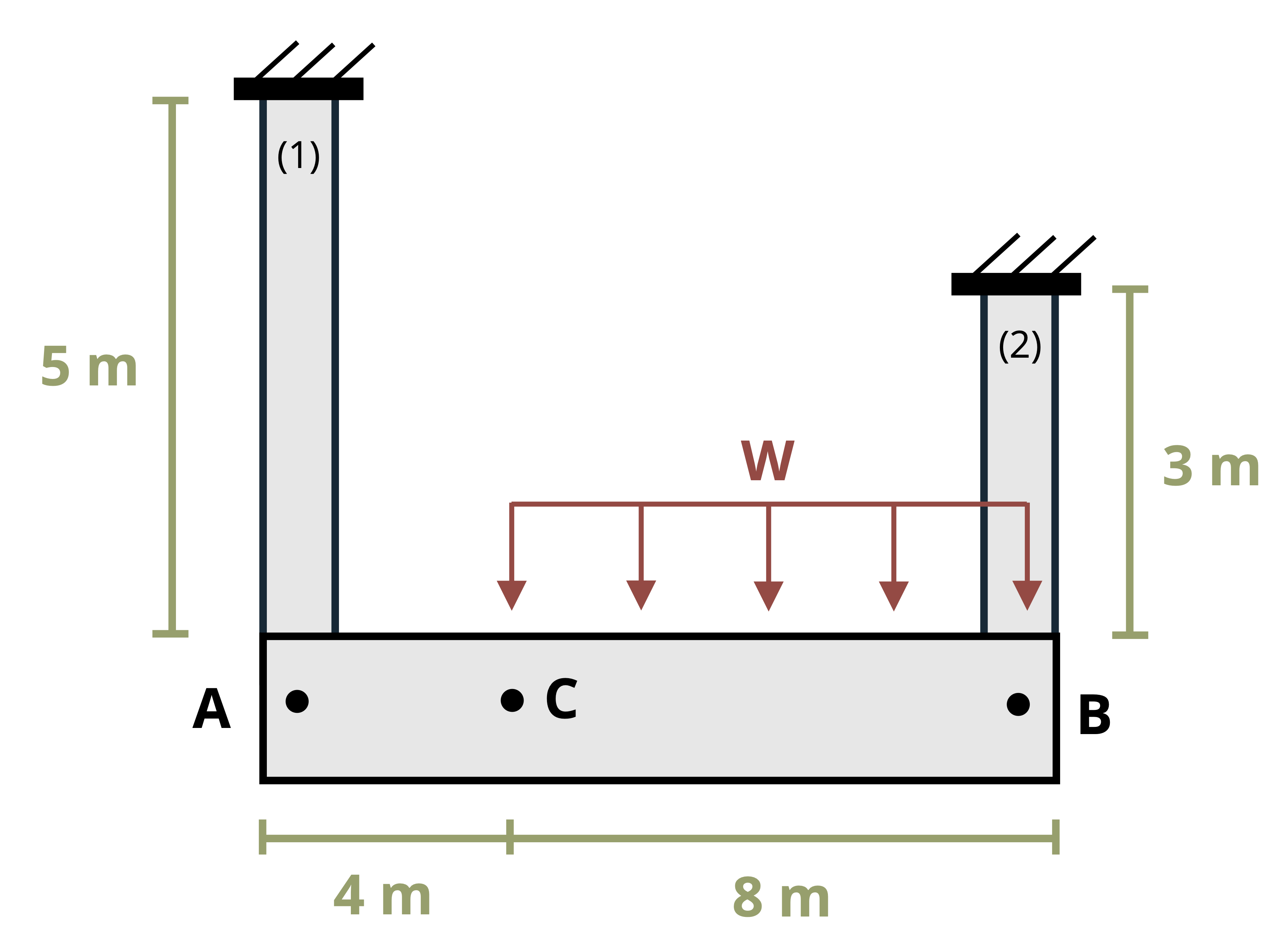

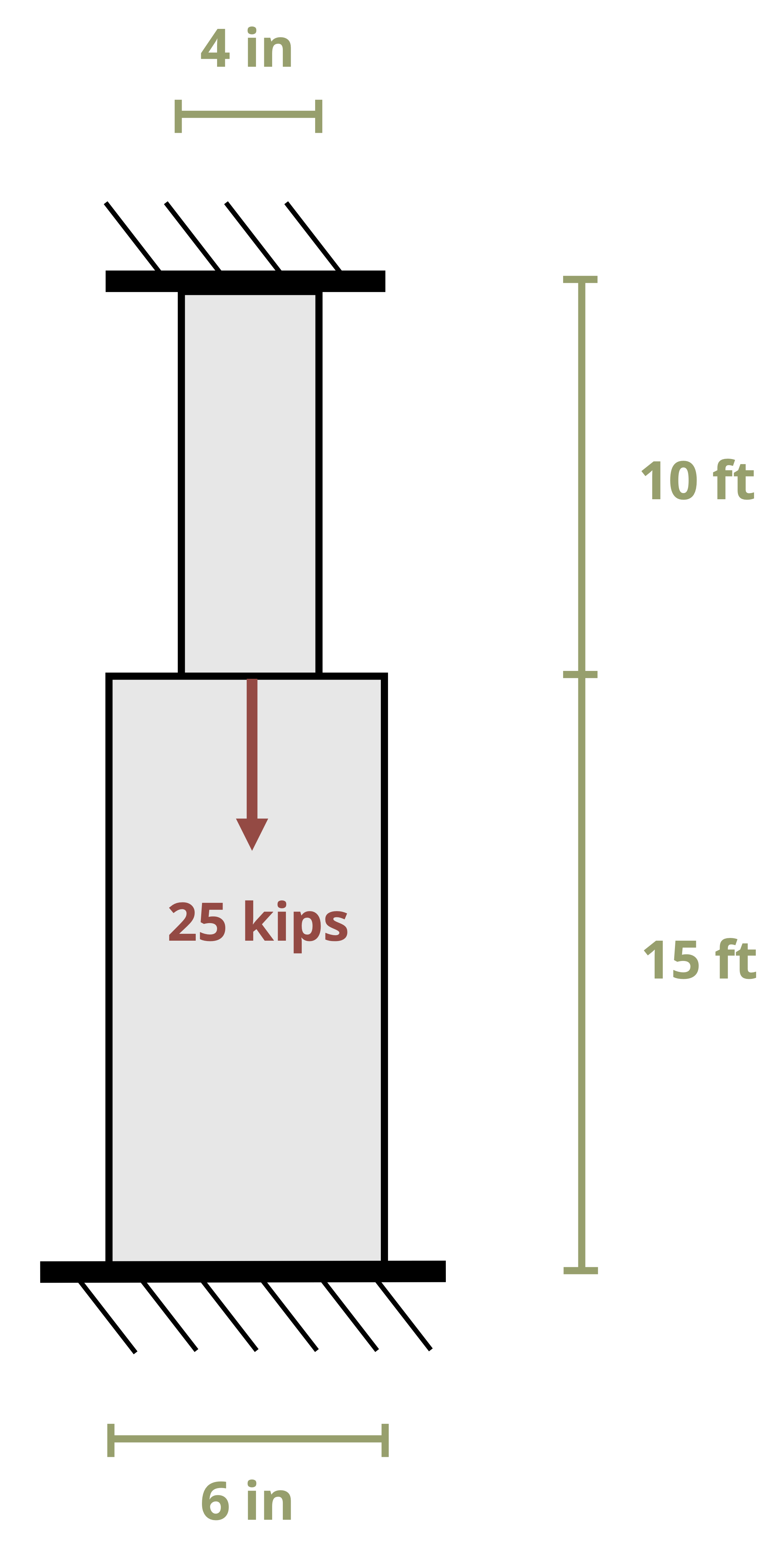

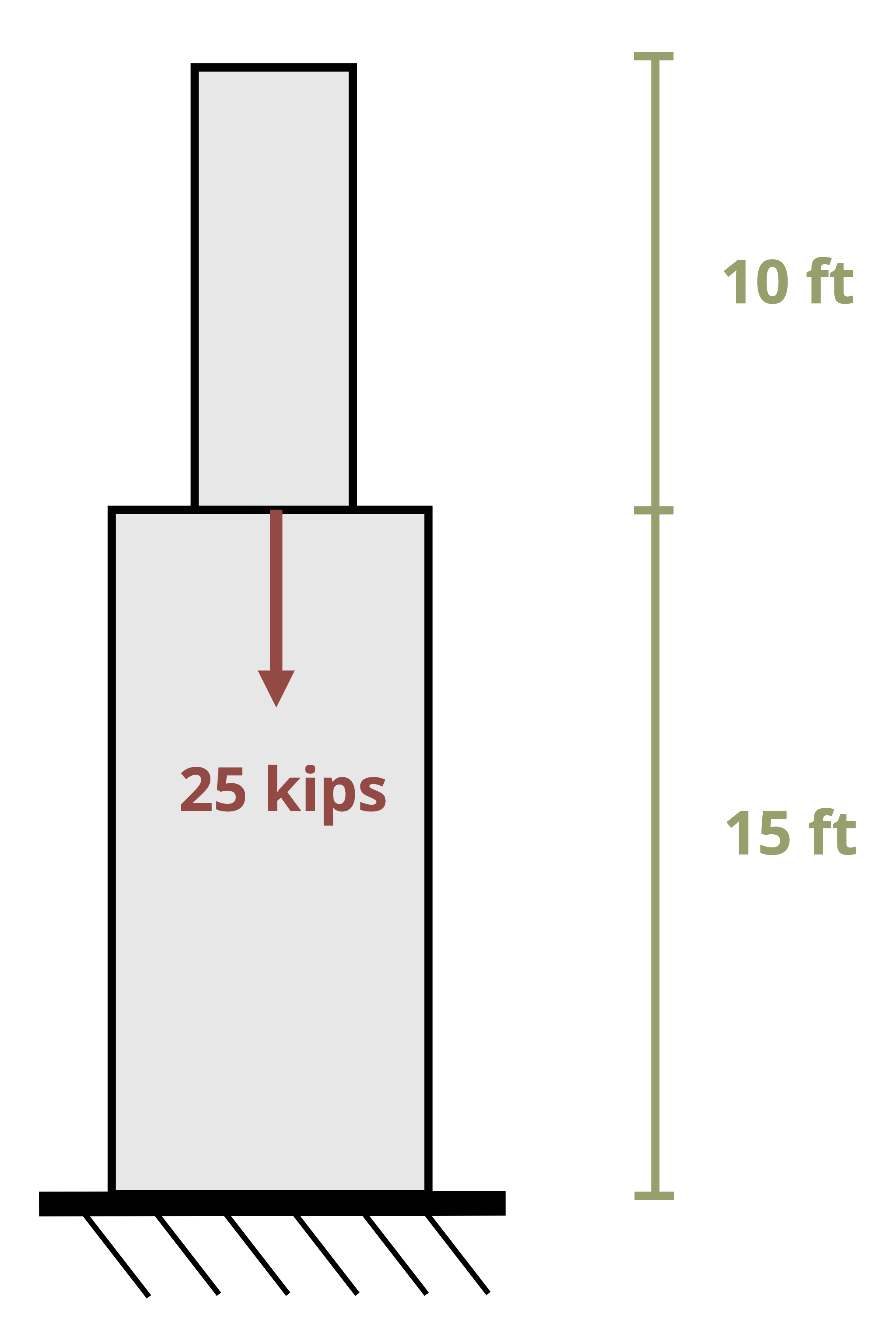

There are two types of statically indeterminate problems. The first type has additional supports beyond those needed to maintain equilibrium. These are known as redundant supports and are quite common in practice (Figure 5.10).

In such problems, determining all the reaction forces using equilibrium alone isn’t possible. However, we can use our knowledge of deformation to help. If a member is held between two supports, then its total deformation must be zero. Since the change in length depends on the internal force in the member, this constraint introduces an additional equation to use alongside the equilibrium equations. Two approaches are possible here.

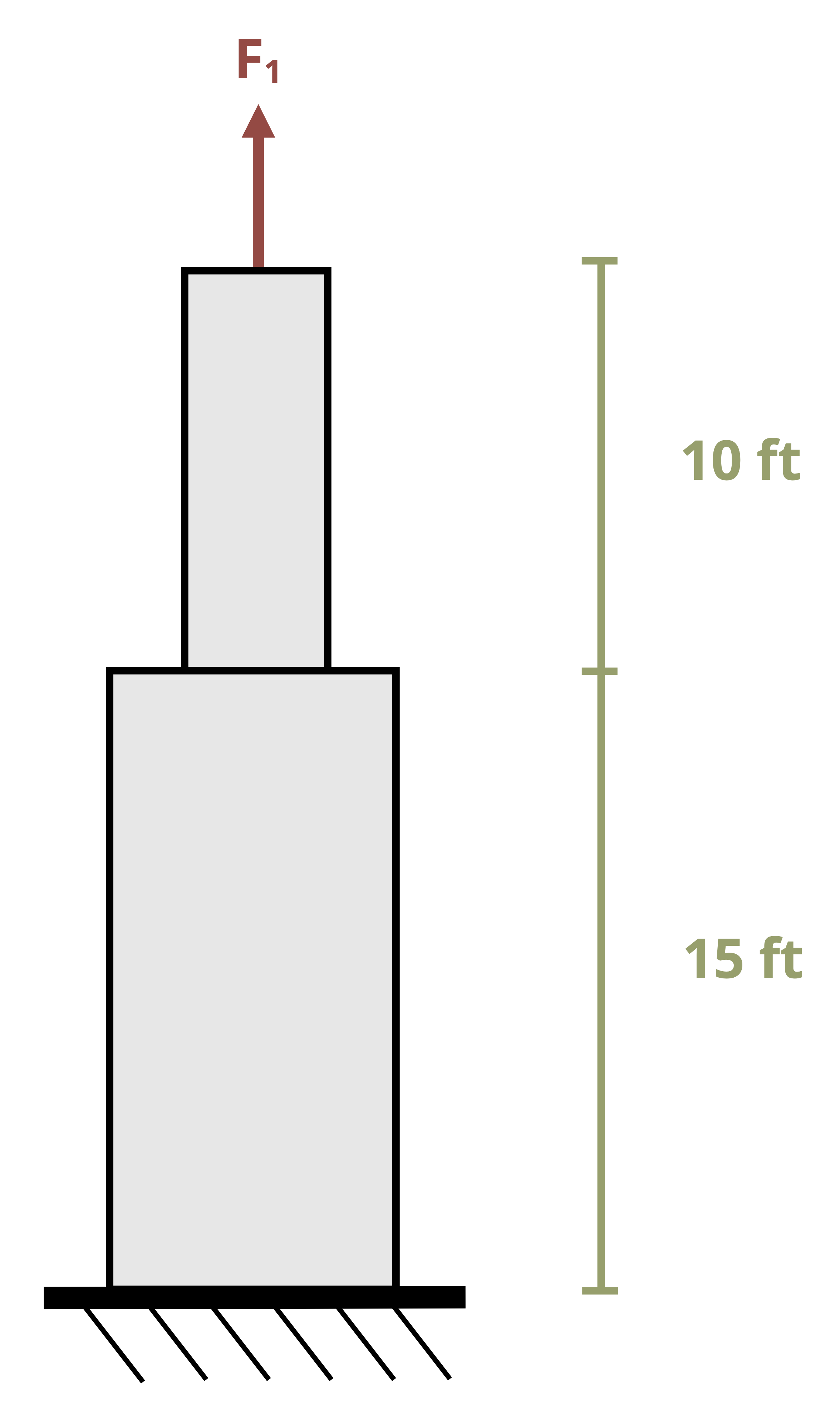

Approach 1: To determine the reaction force at the redundant support, begin by removing the redundant support from the problem and determining the deformation that would occur without the support. Then replace the reaction force at the support, which will cause the member to deform in the opposite direction (Figure 5.11).

The sum of these two deformations must equal the member’s actual deformation. If the member is held between two rigid supports, the total deformation will be zero. If there is a small gap or the supports allow a certain amount of movement, the total deformation will be equal to the size of this gap. Example 5.6 shows this process applied to a bar made of two materials.

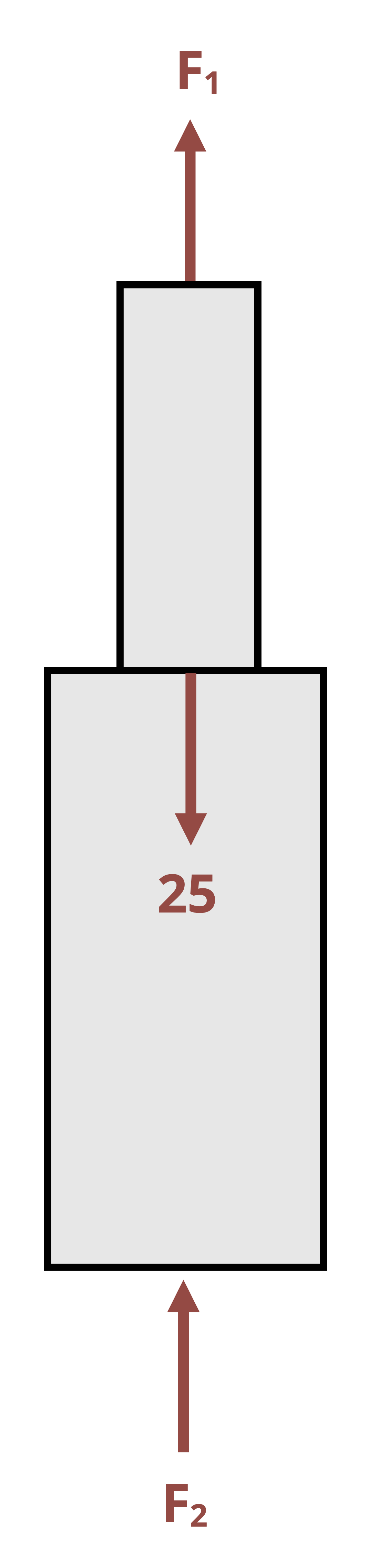

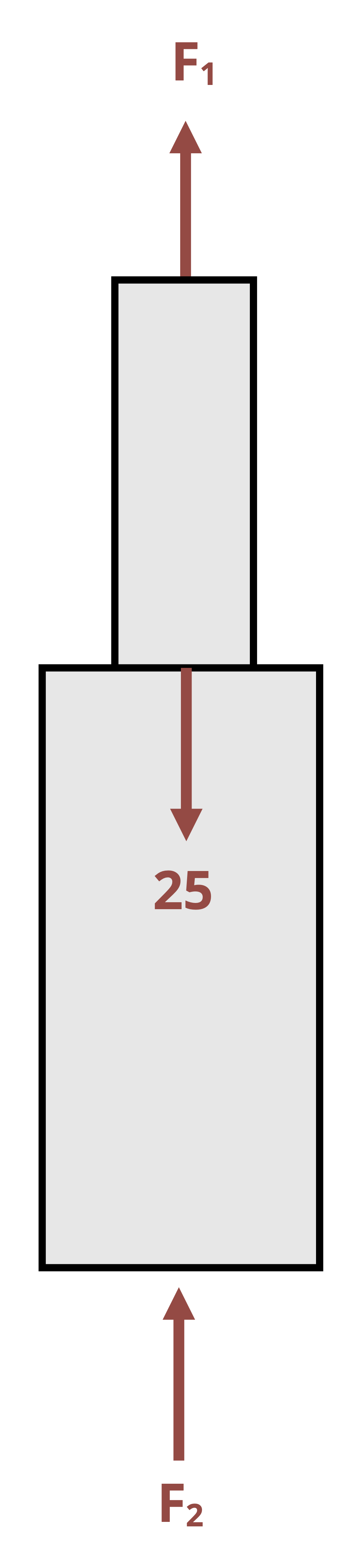

Approach 2: An alternative approach is to start by noting that the total deformation of the bar must be zero. In the case shown in Figure 5.12, the deformation of segment 1 plus the deformation of segment 2 must add up to zero.

The internal load in segment 1 is FA and the internal load in segment 2 is FB, so there are currently two unknowns. We may use an equilibrium equation to solve for these two unknowns simultaneously.

\[ \begin{aligned} & \frac{F_A L_1}{A_1 E_1}+\frac{F_B L_2}{A_2 E_2}=0 \\ \\ & F-F_A-F_B=0\end{aligned} \]

Example 5.7 solves Example 5.6 using this method instead.

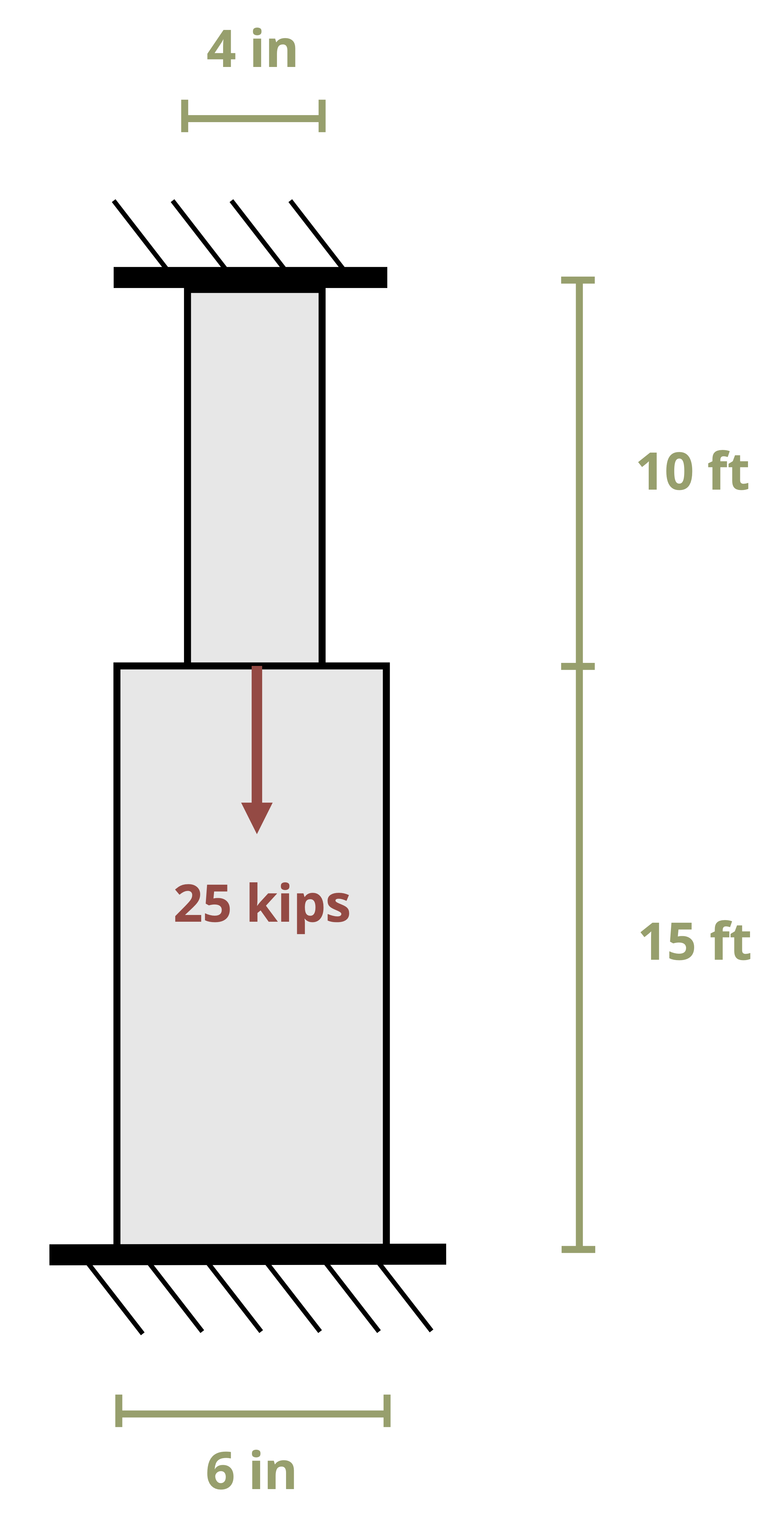

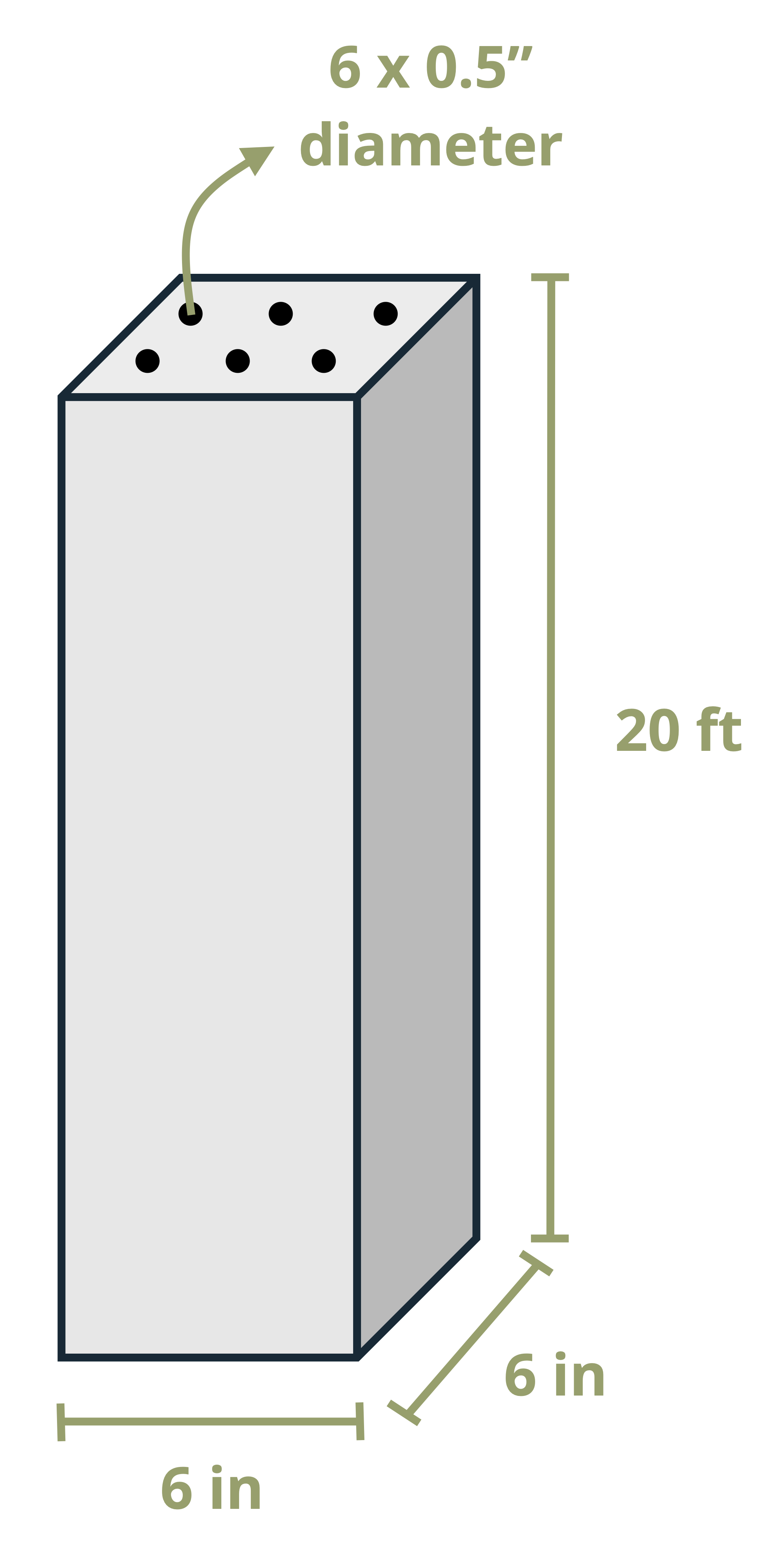

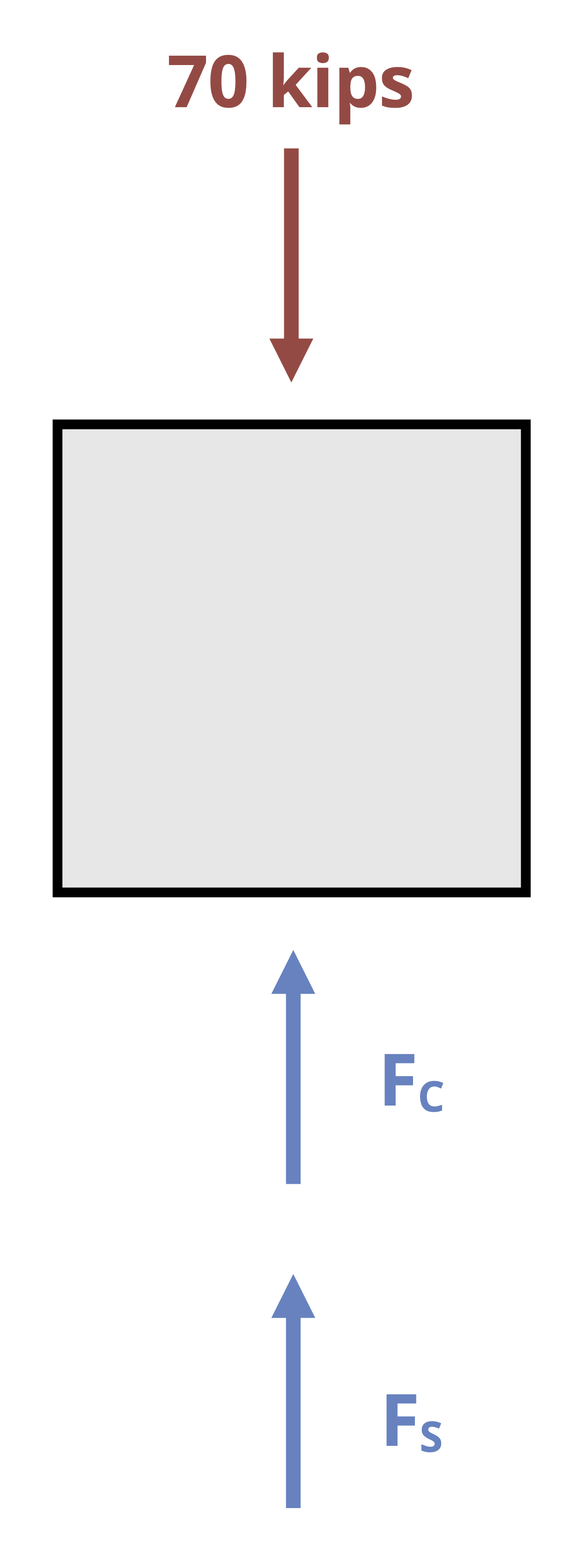

The second type of indeterminate problem involves two materials bonded together in parallel. In these problems it is possible to find the reactions at the supports, but not possible to find the internal force in each material using only equilibrium (Figure 5.13).

We have one equilibrium equation but two unknown internal forces. However, since the materials are bonded together, they must deform by the same amount. By setting the deformation the same for each material, we can define a second equation that involves the two internal forces and, combined with the equilibrium equation, now solve for both internal forces. See Example 5.8 for a demonstration.

5.6 Thermal Deformation and Thermal Stresses

Click to expand

So far we’ve studied the effects of axial forces on an object and how they create stresses and deformations. Temperature changes will also cause an object to deform. As seen in Section 4.6, the strain due to temperature can be predicted by

\[ \varepsilon_T=\alpha \Delta T\text{.} \]

As before, strain is dimensionless. The coefficient of thermal expansion is a material constant that can be looked up in handbooks or in Appendix C. Note that for a given change in temperature, the thermal strain will be the same in the axial and transverse directions.

Since strain is also defined as \(\varepsilon=\frac{\Delta L}{L}\), we can also predict the deformation resulting from a change in temperature.

\[ \varepsilon_T=\alpha \Delta T=\frac{\Delta L}{L} \quad\rightarrow\quad \Delta L=\alpha \Delta T L \]

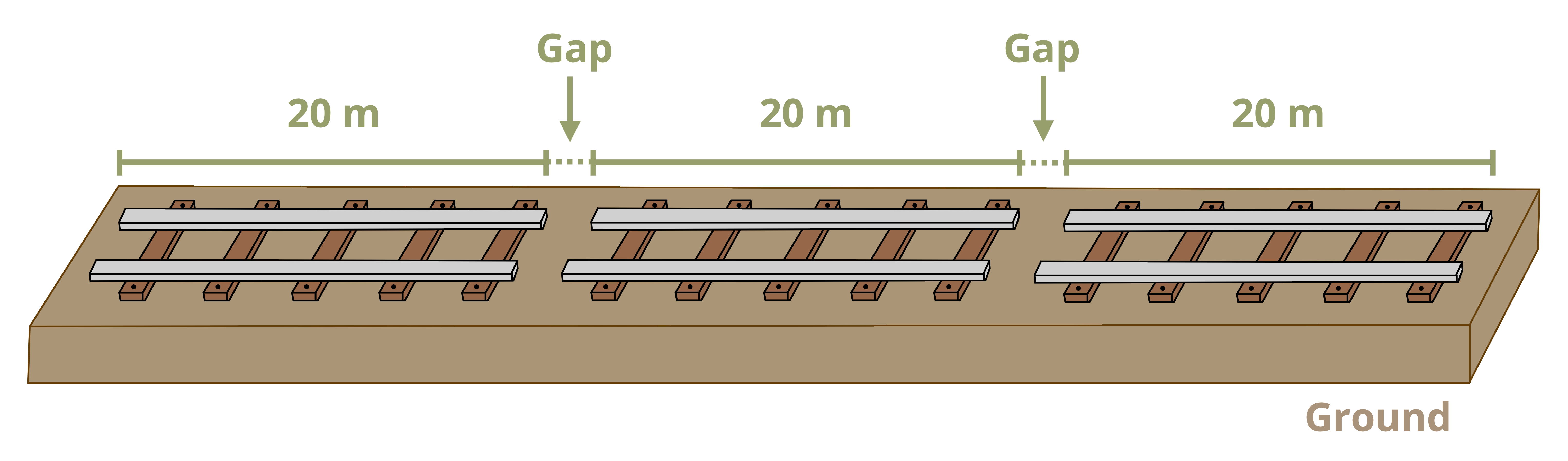

That the object is free to expand or contract doesn’t cause any issues and is easy to account for. Many real applications include a small gap to allow for changes in length due to temperature changes (Figure 5.14). It is even possible that an object is subjected to both a physical force and a temperature change and that the total change in length is simply the sum of these effects.

\[ \boxed{\Delta L=\Delta L_F+\Delta L_T=\frac{F L}{A E}+\alpha \Delta T L}\text{ ,} \tag{5.3}\]

∆L = Change in length [m, in.]

∆LF = Change in length due to applied load [m, in.]

∆LT = Change in length due to temperature change [m, in.]

F = Internal force [N, lb]

L = Original length [m, in.]

A = Original cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

E = Elastic modulus [Pa, psi]

𝛼 = Coefficient of thermal expansion \(\left[\frac{1}{^\circ C}, \frac{1}{^\circ F}\right]\)

∆T = Change in temperature \([^\circ C, ^\circ F]\)

However if we do not design a gap, or if the gap isn’t large enough, then the object is not free to expand or contract. As the member pushes or pulls on its supports, a physical force is created. This in turn creates a stress in the object, and these stresses can be very large. Such problems are statically indeterminate because the force the support applies on the member is unknown and cannot be found using only equilibrium.

Solving these problems is very similar to solving the first type of statically indeterminate problem. First, remove a support and determine the amount of deformation that would occur as a result of the change in temperature if the object were free to deform. Then replace the force from the removed support, which will cause the object to deform in the other direction. The sum of these two deformations will equal the total deformation of the member as before. Example 5.9 works through a statically indeterminate thermal expansion problem.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

Figure 5.2: Each bar has a fixed support on the left, a cross-section of 30 in.², and is subjected to a force of 10,000 lb. James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.

Figure 5.4: The fillet helps prevent a sharp corner but still causes stress concentrations. James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.

Figure 5.5: Graphs showing how the stress concentration factor, K, changes according to the geometry of the object. Adapted under fair use by Kindred Grey from Figures 5.14 and 5.15 in Philpot, T.A. (2020) Mechanics of Materials, 4th Edition, Wiley.

Example 5.1: First and second image: Kindred Grey. 2024. CC BY. Third image: Adapted under fair use by Kindred Grey from Figures 5.14 and 5.15 in Philpot, T.A. (2020) Mechanics of Materials, 4th Edition, Wiley.

Example 5.2: First image: Kindred Grey. 2024. CC BY. Second, third, and fourth image: Adapted under fair use by Kindred Grey from Figures 5.14 and 5.15 in Philpot, T.A. (2020) Mechanics of Materials, 4th Edition, Wiley.

Figure 5.10: An example of redundancy on a suspension bridge. Unknown author. 2017. Public domain. https://pxhere.com/en/photo/759379.

Figure 5.14: Expansion joint on a bridge, allowing for thermal expansion and contraction of the bridge as temperature changes through the year. James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.

![Graph of stress concentration factor K versus hole ratio d/D. The x-axis (0 to 0.8) is d/D (hole diameter to height of the cross section). The y-axis (2 to 3) is K = sigma sub max / sigma sub nom. A blue curve decreases as d/D increases. A red marker at d/D ≈ 0.2 indicates K ≈ 2.5. An inset shows a rectangular plate with a central hole under tension, labeled D (height of the cross section), d (hole diameter), and t (thickness), with K = sigma sub max / sigma sub nom and sigma sub nom = P / [ t (D − d) ].](images/Example 5.1 part 3 NEW.png)

![Graph with the y-axis labeled "Stress-concentration factor K" (ranging from 2 to 3) and the x-axis labeled "Ratio d over D" (ranging from 0 to 0.8). A red vertical line intersects the x-axis at approximately d/D = 0.5, and a red horizontal line intersects the curve at K ≈ 2.15. The blue curve shows that K decreases as the d/D ratio increases. An inset in the top corner shows a rectangular plate with a central hole under tension, labeled with D (plate height), d (hole diameter), and t (thickness). The equation K = sigma sub max / sigma sub nom is shown, with sigma sub nom = P / [ t × (D − d) ].](images/Example 5.2 part 2 NEW.png)